Archaeologists in Israel have discovered five burials in a cave belonging to an enigmatic human lineage that suggest this group shared aspects of its lifestyle, technology and burial customs with modern humans and Neanderthals, who also lived in the region up to 130,000 years ago, a new study reports.

The finding reveals that Neanderthals, modern humans and related human lineages coexisted in what is now Israel for about 50,000 years. However, it’s unknown which group influenced the other and in what direction.

In the new research, scientists investigated caves in the Levant — the eastern Mediterranean region that today includes Israel, the Palestinian territories, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. Researchers have long thought the Levant was a key gateway for our species, Homo sapiens, and other branches of the human family tree that migrated out of Africa.

Prior work suggested that during the mid-Middle Paleolithic (80,000 to 130,000 years ago), the southern Levant was home to at least three different groups of Homo: modern humans, Neanderthals and a third lineage resembling both modern humans and Neanderthals that was unearthed at the prehistoric site of Nesher Ramla in central Israel. Although these groups were physically different from one another, researchers weren’t sure how similar they were in terms of lifestyle.

Artifacts found at Nesher Ramla suggested that the site had been a temporary hunting and butchering camp, so the researchers looked nearby for the main base of operations. “Such sites are usually found in caves,” study lead author Yossi Zaidner, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, told Live Science.

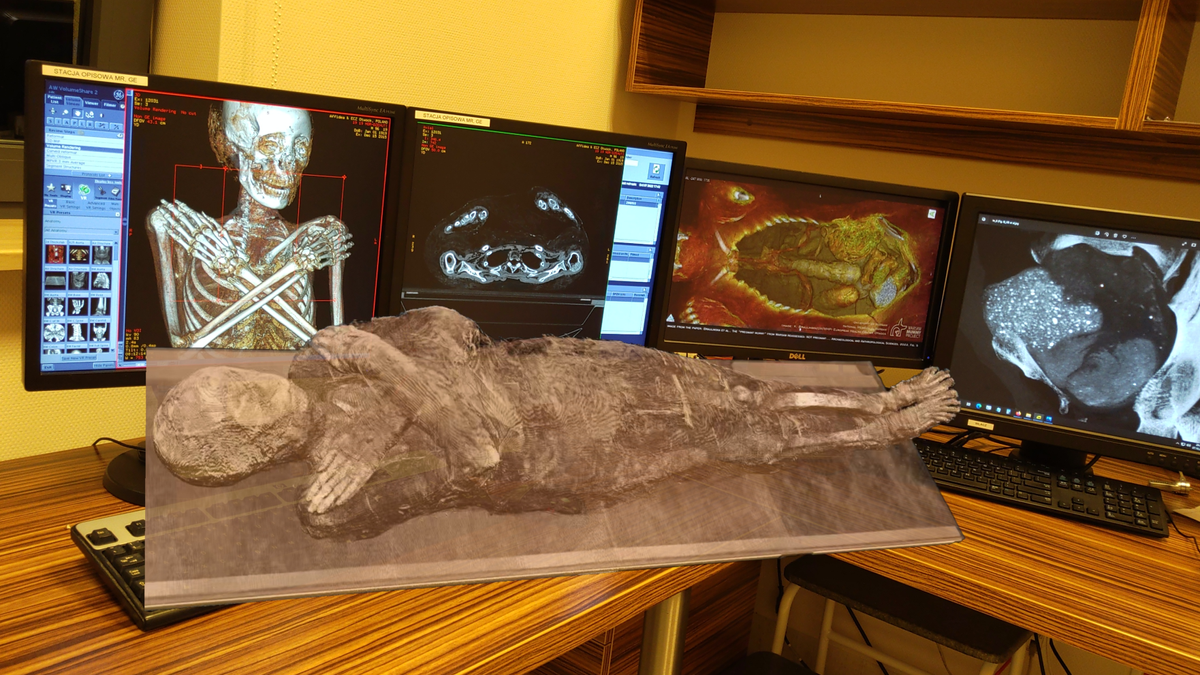

Zaidner and his colleagues focused on Tinshemet Cave about 6 miles (10 kilometers) away from Nesher Ramla. Scientists first discovered the cave in 1940, and new excavations there unearthed five burials belonging to Homo — the first such burials from the mid-Middle Paleolithic found in this region in more than 50 years. It’s currently unknown if these burials belong to early modern humans, human-Neanderthal hybrids, the mysterious other lineage or another group entirely.

Related: Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens buried their dead differently, study suggests

The researchers also uncovered stone artifacts made with the Levallois technique, meaning they are humped on one side, flat on the other and had sharpened edges. In addition, the human remains were buried in fetal positions, often with the red mineral pigment ocher, which prior research suggested was linked with funerary practices and symbolic thought. The scientists also discovered bones of large game such as aurochs (Bos primigenius, an extinct cowlike species), horses, deer and gazelles.

“The discoveries at Tinshemet Cave are probably going to be the most important finds in the region from the last 50 years,” Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science.

Multiple humans at multiple caves

These findings at Tinshemet Cave were very similar to discoveries made in two other caves in Israel — Skhul Cave and Qafzeh Cave — that also date to the mid-Middle Paleolithic. However, the skeletal remains in each cave were significantly anatomically distinct from those of the other caves.

The researchers suggest that different groups of Homo not only coexisted in the mid-Middle Paleolithic in the Levant, but shared a number of key practices, exchanging innovations such as burial rites and the symbolic use of ocher for about 50,000 years. It remains uncertain in which direction these practices were exchanged — say, if modern humans adopted Neanderthal hunting strategies, or if Neanderthals embraced modern human burial rites, or if they came up with new practices together.

“Neanderthals’ and Homo sapiens’ interactions were not just sporadic encounters, but they had very substantial contacts which led to adoption of behaviors,” Zaidner said.

The fact that groups of Homo from this time and place often share anatomical features of both modern humans and Neanderthals suggest “these are actually hybrids that are using the same culture,” Zaidner said.

However, Stringer does not see a mixing of lifestyles. Instead, he suggested the burials and artifacts at the Tinshemet, Skhul and Qafzeh caves are linked only with H. sapiens, and that different behaviors discovered at later Levant sites such as the Kebara, Amud and Dederiyeh caves are linked with Neanderthals.

“That said, there is growing evidence that these populations overlapped in the region about 100,000 years ago more than has been supposed, and given what happened in Europe 50,000 years later, there was clearly potential for contact and both cultural and genetic exchanges,” Stringer said. “I’ve tended to play down the possibility that the Skhul and Qafzeh samples show signs of hybridization with Neanderthals, but they do show a lot of morphological variation, and some of it could indeed be an indication of interbreeding with Neanderthal neighbors.”

The scientists now plan to study the remains at Tinshemet Cave in greater detail to see if they are hybrids of modern humans and Neanderthals, Zaidner said.

“I eagerly await detailed descriptions of the morphology of the Tinshemet fossils,” Stringer said. If interbreeding between modern humans and Neanderthals did happen in the Levant, “and I agree it seems increasingly likely, then somewhere there must be actual first-generation Neanderthal-sapiens hybrids waiting to be discovered or recognized,” Stringer added.

The researchers detailed their findings online Tuesday (March 11) in the journal Nature Human Behavior.