Ching Valdes-Aran in Three Houses, at the Signature.

Photo: Marc J. Franklin

Dave Malloy may be best known for adapting a sprawling 19th-century novel — a portion of War and Peace became Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812 — but lately he’s the leading composer on the subject of hypermodern loneliness, especially the kind experienced online. In Octet, Malloy imagined a support group for people addicted to “the monster” that is the internet. There is a song about being canceled, an acid-tipped upbeat number about Candy Crush, and dark journeys of the soul into online dating and porn. Malloy’s latest work, Three Houses, is more directly about the pandemic, but each of his three primary characters is grappling with a similar beast, those same feelings of intense ever-connectedness and emotional isolation — in this case compounded by the physical isolation of lockdown. Each character introduces their third of the musical with the same refrain, like cantors repeating a bit of liturgy: “During the pandemic, when the lockdown hit.”

The second member of Malloy’s trio, the chipper Sadie (Mia Pak), responds to the pandemic in the way that a character from Octet might: by constructing an elaborate recreation of her grandmother’s house inside a video game. (The obvious inspiration is the early-2020 obsession with Animal Crossing, though there are also elements of Stardew Valley and The Sims.) The game provides a level of comfort and systemization the outside world simply does not allow, even as it also further alienates Sadie from that world. Listening to her describe her blossoming obsession, you feel thrown back to that same emotional darkness, as well as the creeping crescendo of one realm — the synthetic, full of instant gratification — becoming more real than actual reality. “See there’s this clicking in my head when certain things line up,” she sings, “when like is put with like / and there is order.”

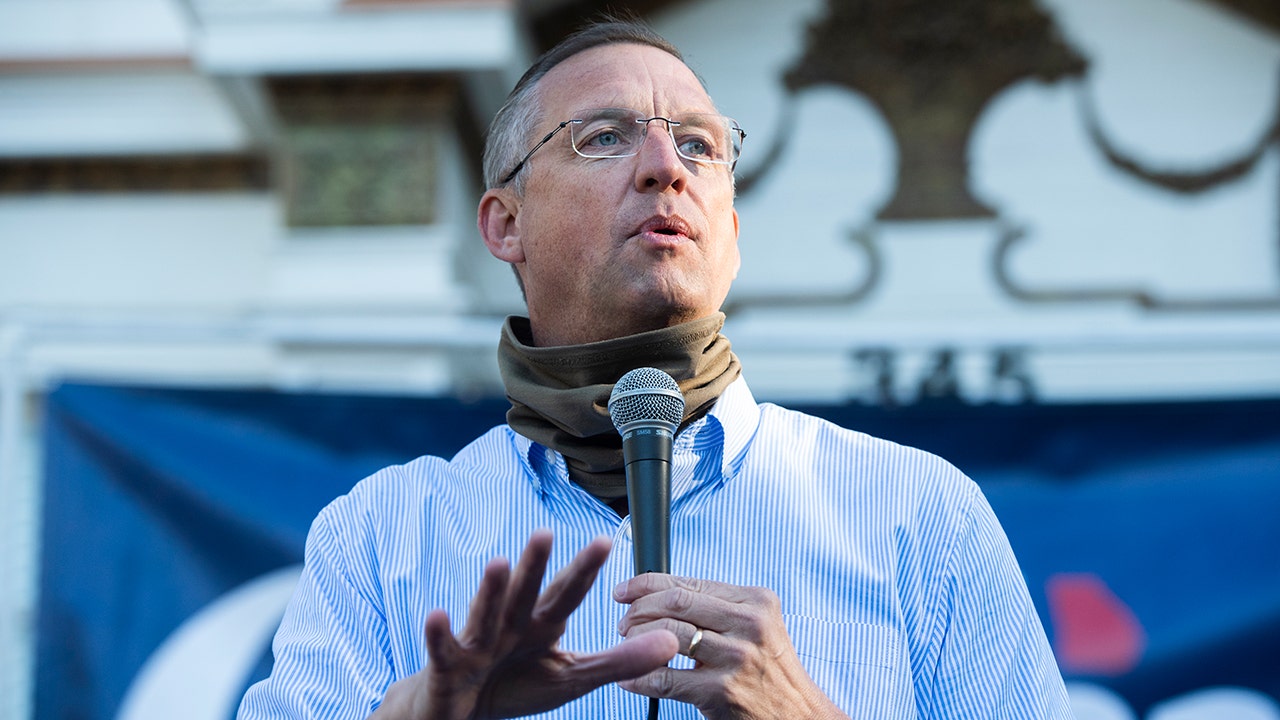

The quest for order, self-destructive as it may become, haunts all three characters in Three Houses, though each expresses it in their own way. Keeping to an overarching metaphor of the Three Little Pigs, Malloy imagines three strangers gathering in a bar, which the design team dots — omnipresent and double Tony nominated — has styled with the cozy retro familiarity of Cheers for a kind of karaoke night. The evening is run by a menacing emcee known as the Wolf (Scott Stangland, who gives a good I-swallowed-your-grandma grin through his thick beard). The Wolf hands the first guest, Susan (Margot Seibert, louchely devil-may-care), a straw, and then she sings about her lockdown at her grandmother’s home in Latvia; he gives the second, Pak’s gaming-addicted Sadie, a swizzle stick, and she sings about her lockdown at her aunt’s home in Taos, New Mexico; then he slams a brick down in front of the third, Beckett (J.D. Mollison, nervy and confrontational), who was stuck in a basement apartment in Brooklyn. Each actor takes the spotlight to tell their story for their third of the show, while the others accompany them, alongside Henry Stram and Ching Valdes-Aran, who play the recurring figures of each character’s grandfather and grandmother.

Malloy is working in the realm of fairy tales and fables, allowing echoes to accumulate among the three main tales. Annie Tippe, directing (she also did Octet and Malloy’s earlier Ghost Quartet), conjures a mood that’s somewhere between a 2 a.m. barroom truth-spilling and formal spiritual confession. All three characters experienced breakups right before March 2020, and each of their new obsessions — whether it’s gaming; trying to organize a Latvian grandmother’s library, as in Seibert’s case; or repeatedly ordering New Age charms on Amazon, as in Mollison’s — takes root in those untreated interpersonal wounds. Malloy will allow a character to deliver a monologue in song, as Seibert does, achingly describing the throng of birch trees around her in Latvia before introducing a riptide of repressed feeling that pulls them and the music in an opposite direction. As Seibert sings about her pastoral bliss, she elides the mess she’s made of her personal and professional life — she skips a lot of work Zooms — and distracts herself with weed and booze until her demons (she’s a lot more responsible for that breakup than she’d initially care to admit) are too difficult to ignore. It’s impressively well-observed music of self-delusion, which requires agile performances, both emotionally and vocally. Tippe (as well as musical director Or Matias) crucially makes sure that no one in the cast overanticipates the turns to come. We skip along, for a bit, until the wolf bares his teeth.

Malloy’s work is, as always, precisely rendered as it wanders a full emotional range from giddiness to horror, but the musical’s obsession with order threatens to undermine its own emotional force. It’s structured in three sections, each with seven parts, followed by a coda. The resonances (breakups, grandparents, fables) link the sections together, and they become too strict and neat. Every character talks to a puppet — a cute Latvian dragon, a game character, a giant spider named Shelob (I may have been the only one to laugh at the Ungoliant joke). It’s a clever conceit; it’s also a lot of puppets. Stephen Sondheim, writing about the dreamlike “Loveland” section of Follies, once offered that the danger of giving an audience too clean of a set of repetitions is that they tune out and start counting down the series. Even with only a trilogy of stories, Three Houses left me doing precisely that: Okay, here’s the description of the breakup, here’s the introduction of the grandparents, here’s the puppet. It might be satisfying, in a “clicking in your head” way, to construct a work so that all the elements line up, but it’s less satisfying to watch. Mollison, telling the third of those three stories, eventually participates in a rebellion against the format, with the help of the other two storytellers. But his reckoning with the big bad wolf, at that point, has its own air of inevitability — of course a fable must end with a twist and a new form of harmony. What would happen instead if the story didn’t slide into place and kept wandering?

The characters in The Lonely Few are also looking for a way to rip away their isolation through song, though their predicament is more about class and politics than a pandemic. In Zoe Sarnak’s musical, which has a book by Rachel Bonds, Lila (Lauren Patten, who you may remember belting “You Oughta Know” in Jagged Little Pill) is a young lesbian woman fronting a rock band in a small Kentucky town. She’s writing about dead-end dreams, the emotion expressed through her lyrics — “night by night, we sing a prayer to the God of Nowhere,” goes the opening number, “night by night, we crawl inside the song” — but more pressingly by the searing yawp of Patten’s voice when she lays into a big note. Lila has something in her that’s burning her up, too big for her own context. (It’s also too big, maybe, for the small space of MCC Theater; earplugs are offered at the door.)

Lauren Patten and Taylor Iman Jones in The Lonely Few.

Photo: Joan Marcus

While Sarnak’s music — awash with yearning that drowns out its less precise imagery — and this cast’s performances provide The Lonely Few with rock-operatic charge, the musical itself gets sluggish, and that’s largely because Bonds’s book is really predictable. One day, a star on tour named Amy (Taylor Iman Jones, with a typhoon of a voice of her own; she’s a graduate of Six) ends up at Lila’s bar. They talk shop and, of course, flirt. Soon Lila and her bandmates (including a peppily naïve Helen J. Shen and a surprisingly dweeby Damon Daunno) are headed out on tour with Amy, leaving her troubled brother Adam (Peter Mark Kendall) behind. Lila — big surprise — ends up torn between her obligations to her family and her rock-star dreams.

These generic tropes can be satisfying if they’re filled in with human detail, but The Lonely Few has only amped-up volume. Nearly every exchange between Lila and Amy is about small-town prejudices (“and you know … I’m black, I’m queer, it’s the South,” goes one of Amy’s lines), to the extent that you wonder if they ever talk about anything else. Trip Cullman and Ellenore Scott’s direction, similarly rote and presentational, leaves the actors at sea trying to get beyond generic character sketches, and sometimes they seem as if they are just reading statistics about rural life. (Thomas Silcott, as a paternal figure to both Lila and Amy, fares the best.) I kept thinking about the far more complex vision of Middle American dreaming seen in Bridget Everett’s Somebody Somewhere or the eccentric queer madness of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, to which Saynak’s music owes a debt. In those stories, comfort and invention overlap simultaneously with oppression and conformity; it’s possible for one small town to contain many things at once. The Lonely Few doesn’t look so closely. There isn’t much space to vary your dynamics when the sound is blown out.

Three Houses is at Signature Theatre.

The Lonely Few is at MCC Theater.