Skull cups and skeleton masks have been discovered among a pile of 5,000-year-old discarded human bones in China, according to a new study.

The sculpted skulls were found jumbled up with pottery and animal remains, but the purpose of the macabre items has so far eluded experts.

Several Liangzhu cemeteries have been discovered in the past, but none of them had sculpted bones. Archaeologists recovered more than 50 individual human bones from canals and moats at five sites that show signs of being “worked” — split, perforated, polished or ground down with tools.

“The fact that many of the worked human bones were unfinished and discarded in canals suggests a lack of reverence toward the dead,” study lead author Junmei Sawada, a biological anthropologist at Niigata University of Health and Welfare in Japan, told Live Science in an email.

There were no traces of the bones coming from people who died violent deaths, or signs that the skeletons had been pulled apart. That means the bones were likely processed after corpses decomposed, Sawada said.

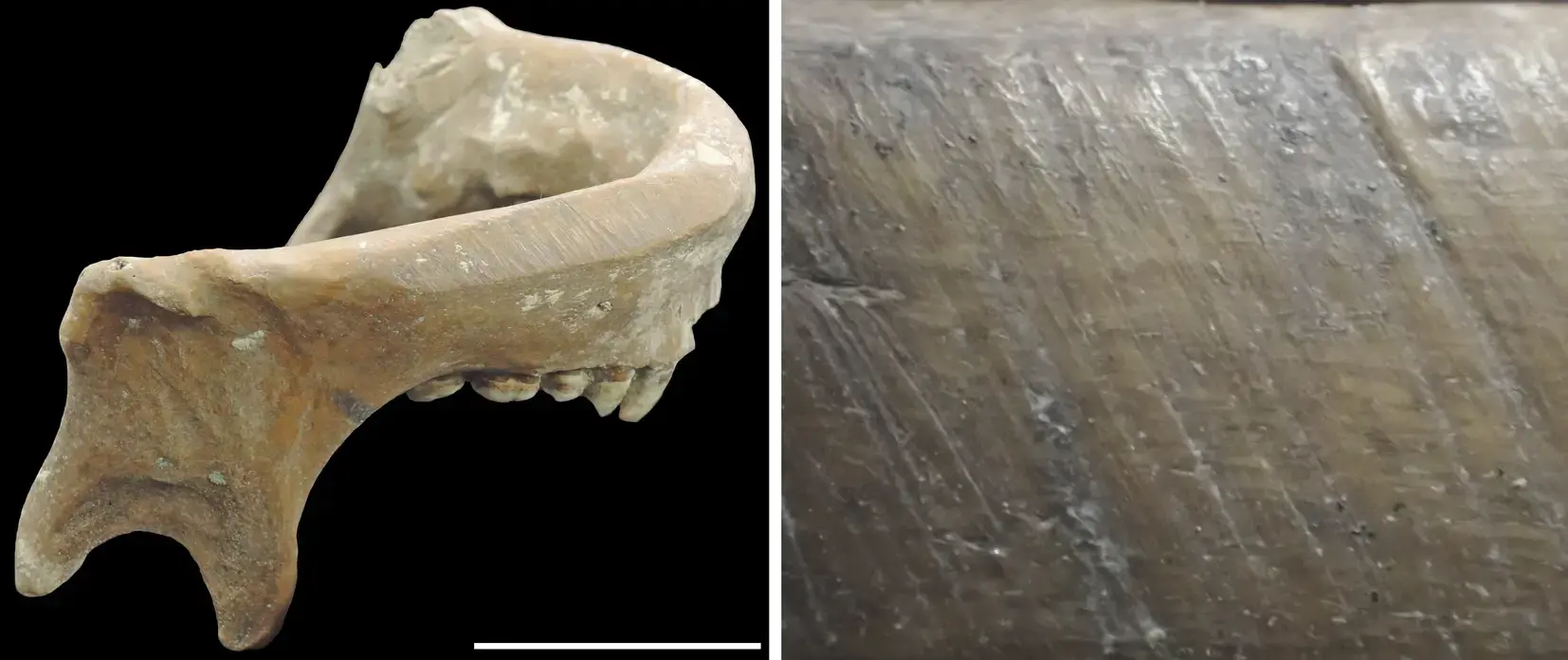

The researchers discovered that the most common worked bone was the human skull. They found four adult skulls that had been cut or split horizontally to create “skull cups,” and another four skulls that were split top-to-bottom to create a skeleton mask-like object.

Human skull cups have been previously recovered from high-status Liangzhu culture burials, the researchers wrote in the study, which suggests that they may have been made for religious or ritualistic purposes.

The mask-like facial skulls, however, have no parallel. And other types of discarded worked bone, including a skull with perforations on the back and a lower jaw that had been purposefully flattened, are also unique.

“We suspect that the emergence of urban society — and the resulting encounters with social ‘others’ beyond traditional communities — may hold the key to understanding this phenomenon,” Sawada said.

Because many of the worked bones are unfinished, this suggests that human bones were not particularly rare or significantly valued, according to the study, which highlights a transformation in the perception of the dead during the swiftly urbanizing Liangzhu culture. When people no longer know all their neighbors or count them as kin, it may be easier to separate bones from the people they belonged to, the study authors suggested.

“The most interesting and unique thing about the findings is the fact that these worked human bones were essentially trash,” Elizabeth Berger, a bioarchaeologist at the University of California, Riverside, told Live Science. Berger agreed with the researchers that the atypical treatment of the bones might be related to the increasing anonymity of an urban society.

The Liangzhu culture’s practice of working human bones appeared suddenly, lasted for at least 200 years based on radiocarbon dates, and then disappeared, the researchers wrote.

“The people of Liangzhu came to see some human bodies as inert raw material,” Berger said, “but what caused that to happen and why did it only last for a few centuries?”

Sawada said that future studies may help address these questions, particularly by helping reveal when and how people sourced the bones. These additional analyses could help the researchers tease out the meanings behind the practice and its relationship to changing social ties and kinship in Neolithic China.