Despite decades of research focusing on obesity, what happens in the body when we lose weight, and why losing weight can improve health, is still poorly understood.

Now a new study, published in Nature on Wednesday (July 9), provides clues as to what may actually be happening. It suggests that the weight loss does more than shave off pounds — it changes fat on a cellular level, rewiring how the tissue is metabolized and maybe even “rejuvenating” it.

The research also offers insights into why losing weight does not necessarily eliminate all the health problems associated with obesity. The study found that some markers of poor health in obesity, such as cells that drive inflammation, were not resolved after weight loss.

“What we’re excited by is being able to really understand the ‘yins and yangs’ of weight loss,” study lead author William Scott, an obesity researcher from Imperial College London, told Live Science.

Thanks to this kind of research, “we may, in the future, be able to develop drugs that target the good bits, but also block the harmful bits that get hardwired by obesity,” he added.

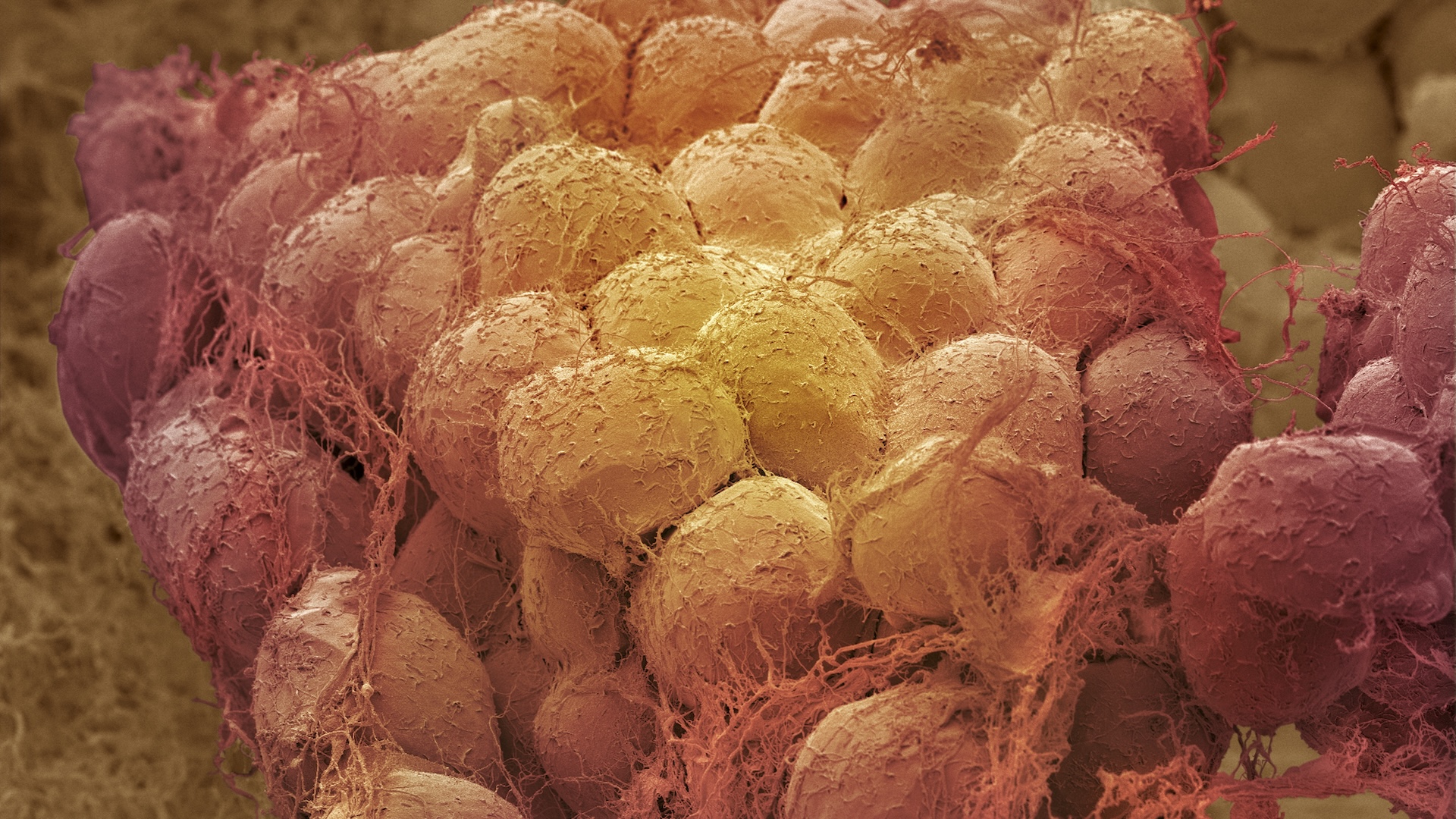

Zooming in on fat cells

To understand what may be happening in fat cells when people lose weight, Scott and his colleagues collected samples of subcutaneous abdominal fat — fat that grows under the skin around the belly — from 25 volunteers with obesity before and after weight-loss surgery. The samples were collected between five and 18 months post-surgery, when the participants had lost an average of 55 pounds (25 kilograms) and were still in an “active” weight loss phase, said Scott.

Related: Fat cells have a ‘memory’ of obesity, study finds

The samples were compared to tissues collected from 24 lean volunteers whose body mass indices were in the “normal” range. They also compared the data to a previously published “atlas” of all the white fat in the body, which also cataloged the chemical processes occurring in that fat tissue.

The scientists then studied how weight loss affected cell activity. They measured which genes were active in each cell by looking at their RNA molecules. RNA is a cousin of DNA that copies down information from genes and serves as the blueprint for proteins, so looking at which RNAs are present and how many can be used as a measure of gene activity. This method, called single nucleus RNA sequencing, reveals what the cells were about to do when sampled, and how they were interacting with each other at the time.

Getting that level of insight into the fat tissue is important because, contrary to popular belief, it is not a monolithic, passive mass. Instead, it is made up of many cell types — fat cells (also called adipocytes), immune cells, vascular cells and nerve cells — that work together. These diverse cells send signals to the body and brain, helping regulate metabolism, appetite and overall health.

Altogether, the study analyzed the RNA expression of more than 170,000 cells in the fat tissues.

Reversing aging and recycling fatty molecules

The study showed that fat tissue in larger bodies tends to be prone to “senescence,” meaning some cells act aged and are more damaged than younger cells. Scientists suspect these senescent cells may fuel the diseases associated with obesity, as they promote inflammation and fibrosis, or scarring.

However, in weight loss, that senescence seems to be reversed, and the tissue appears healthier.

“The body clears damaged and harmful cells and, in effect, is rejuvenating our tissues,” Scott said. “We weren’t really surprised by that,” as this had been hinted at in other studies, “but we were surprised by the extent to which that seems to happen.”

Furthermore, weight loss seems to change the way the fat cells interact with fatty molecules, called lipids. High lipid levels in the blood can harm the body. When storage capacity within fat tissue is exceeded, lipids accumulate in other tissues like the liver and pancreas, likely contributing to insulin resistance, liver disease and diabetes.

The new research suggests that fat cells not only break down lipids, but also recycle them, using the components to make new fatty molecules. This process may burn energy, helping with weight loss, and may also keep harmful fats from building up in other organs and causing problems.

Some cellular changes associated with obesity weren’t reversed, however. The researchers noticed that immune cells, which infiltrate fat tissue and drive disease in obesity, were still present after weight loss.

“We found that obesity hard wires some of the processes in the cells,” Scott said. “There’s a memory in fat tissue.” That means that losing weight is “never going to be as good” as maintaining a healthy weight in the first place.

Andrew Hoy, a lipid metabolism researcher at the University of Sydney who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science by email that the method the team used doesn’t capture all the complex cellular interactions that may be at play. As such, it can’t say for sure that fat cells are being “rejuvenated” or that immune cells remain after weight loss, he said.

What’s more, the study only looked at subcutaneous fat, but visceral fat, which surrounds internal organs, is known to be more closely linked with disease. So studying visceral fat may be more helpful for determining what drives disease in obesity, Hoy argued.

Scott added that the study cannot explain what drives the observed changes in fat tissues during weight gain or loss. He hopes that further research would help show what is happening at different stages of weight loss and gain, as well as when weight plateaus.

It may also be that the weight loss surgery helped usher the cellular changes and weight loss at the same time, rather than the weight loss itself driving the changes, suggested Dr. Francesco Rubino, a metabolic surgery researcher at King’s College London in the U.K. who wasn’t involved in the study.

He told Live Science in an email that he thinks the work supports the idea that dramatic weight loss, by itself, should not be the sole goal of obesity treatment. His and other research suggests that gains to metabolic health can happen even with modest weight loss, and that the metabolic improvements are the important bit.

“We assume that there is a proportion between weight loss and outcomes. That, I think, is a fundamental mistake,” Rubino told Live Science. “You shouldn’t judge the success of treatment based only on weight loss, because you might lose less weight and still achieve fantastic benefits,” he added.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.