Author John Green has been obsessed with tuberculosis (TB) since 2019, when he first visited Lakka Government Hospital in Sierra Leone and met a young TB patient named Henry Reider. In his latest book Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection (Crash Course Books, 2025), Green explores the history of the bacterial disease, highlighting its impact in different eras of history. And he calls attention to the present reality of TB, a curable disease that nonetheless kills over a million people each year due to stark health care inequities around the globe.

In this day and age, Green argues that injustice is the root cause of TB cases and deaths, and that we can collectively choose to correct that injustice and finally snuff out the deadly disease.

Related: ‘We have to fight for a better end’: Author John Green on how threats to USAID derail the worldwide effort to end tuberculosis

At the time, I knew almost nothing about TB. To me, it was a disease of history — something that killed depressive 19th-century poets, not present-tense humans. But as a friend once told me, “Nothing is so privileged as thinking history belongs to the past.”

When we arrived at Lakka, we were immediately greeted by a child who introduced himself as Henry. “That’s my son’s name,” I told him, and he smiled. Most Sierra Leoneans are multilingual, but Henry spoke particularly good English, especially for a kid his age, which made it possible for us to have a conversation that could go beyond my few halting phrases of Krio. I asked him how he was doing, and he said, “I am happy, sir. I am encouraged.” He loved that word. Who wouldn’t? Encouraged, like courage is something we rouse ourselves and others into.

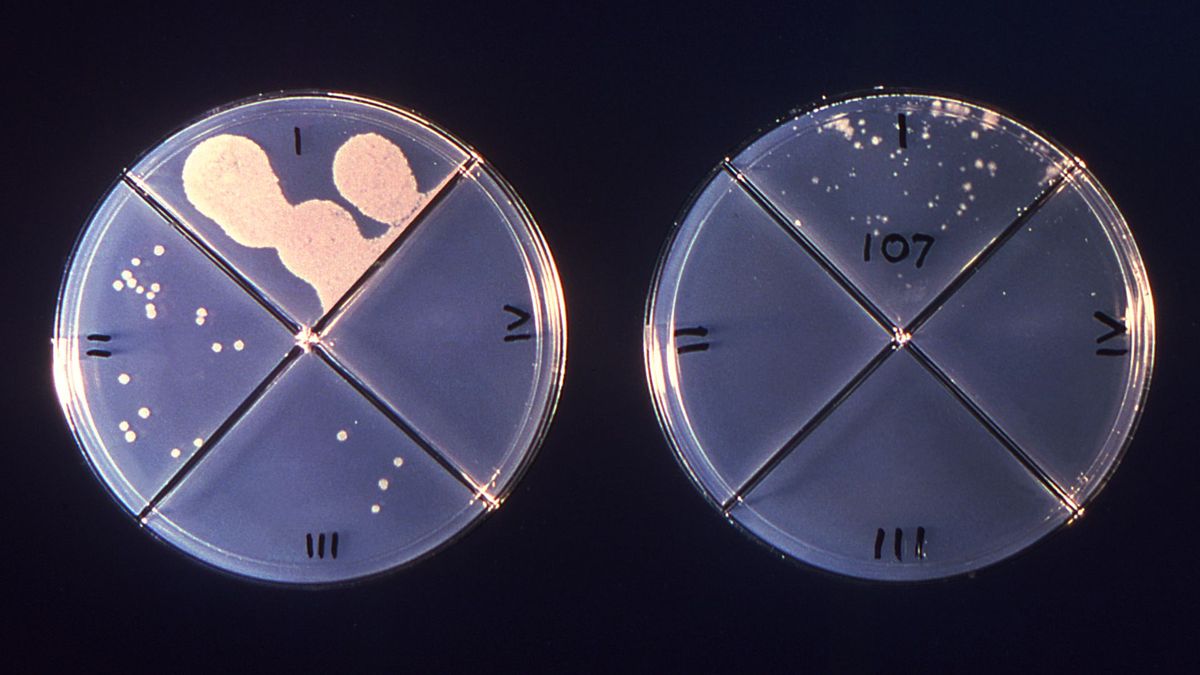

My son Henry was 9 then, and this Henry looked about the same age — a small boy with spindly legs and a big, goofy smile. He wore shorts and an oversized rugby shirt that reached nearly to his knees. Henry took hold of my T-shirt and began walking me around the hospital. He showed me the lab where a technician was looking through a microscope. Henry looked into the microscope and then asked me to, as the lab tech, a young woman from Freetown, explained that this sample contained tuberculosis even though the patient had been treated for several months with standard therapy. The lab tech began to tell me about this “standard therapy,” but Henry was pulling on my shirt again. He walked me through the wards, a complex of poorly ventilated buildings that contained hospital rooms with barred windows, thin mattresses, and no toilets. There was no electricity in the wards, and no consistent running water. To me, the rooms resembled prison cells. Before it was a TB hospital, Lakka was a leprosy isolation facility — and it felt like one.

Inside each room, one or two patients lay on cots, generally on their side or back. A few sat on the edges of their beds, leaning forward. All these men (the women were in a separate ward) were thin. Some were so emaciated that their skin seemed wrapped tightly around bone. As we walked down a hallway between buildings, Henry and I watched a young man drink water from a plastic bottle, and then promptly vomit a mix of bile and blood. I instinctively turned away, but Henry continued to stare at the man.

I figured Henry was someone’s kid — a doctor, maybe, or a nurse, or one of the cooking or cleaning staff. Everyone seemed to know him, and everyone stopped their work to say hello and rub his head or squeeze his hand. I was immediately charmed by Henry — he had some of the mannerisms of my son, the same paradoxical mixture of shyness and enthusiastic desire for connection.

Henry eventually brought me back to the group of doctors and nurses who were meeting in a small room near the entrance of the hospital, and then one of the nurses lovingly and laughingly shooed him away.

“Who is that kid?” I asked.

“Henry?” answered a nurse. “The sweetest boy.”

“He’s one of the patients we’re worried about,” said a physician who went by Dr. Micheal.

“He’s a patient?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“He’s such a cute little kid,” I said. “I hope he’s going to be okay.”

Dr. Micheal told me that Henry wasn’t a little boy. He was seventeen. He was only so small because he’d grown up malnourished, and then the TB had further emaciated his body.

“He seems to be doing okay,” I said. “Lots of energy. He walked me all around the hospital.”

“This is because the antibiotics are working,” Dr. Micheal explained. “But we know they are not working well enough. We are almost certain they will fail, and that is a big problem.” He shrugged, tight-lipped.

There was a lot I didn’t understand.

After I first met Henry, I asked one of the nurses if he would be okay. “Oh, we love our Henry!” she said. She told me he had already gone through so much in his young life. Thank God, she said, that Henry was so loved by his mother, Isatu, who visited him regularly and brought him extra food whenever she could. Most of the patients at Lakka had no visitors. Many had been abandoned by their families; a tuberculosis case in the family was a tremendous mark of shame. But Henry had Isatu.

I realized none of this was an answer to whether he would be okay.

He is such a happy child, she told me. He cheers everyone up. When he’d been able to go to school, the other kids called him pastor, because he was always offering them prayers and assistance.

Still, this was not an answer.

“We will fight for him,” she told me at last.

Editor’s note: This excerpt, from Chapter 1 of “Everything is Tuberculosis,” has been shortened for the purpose of this reprinting.