Astronomers have discovered that the “dark sides” of Uranus‘ largest moons aren’t where they originally thought — and in some cases are on the complete opposite sides of the icy satellites than expected.

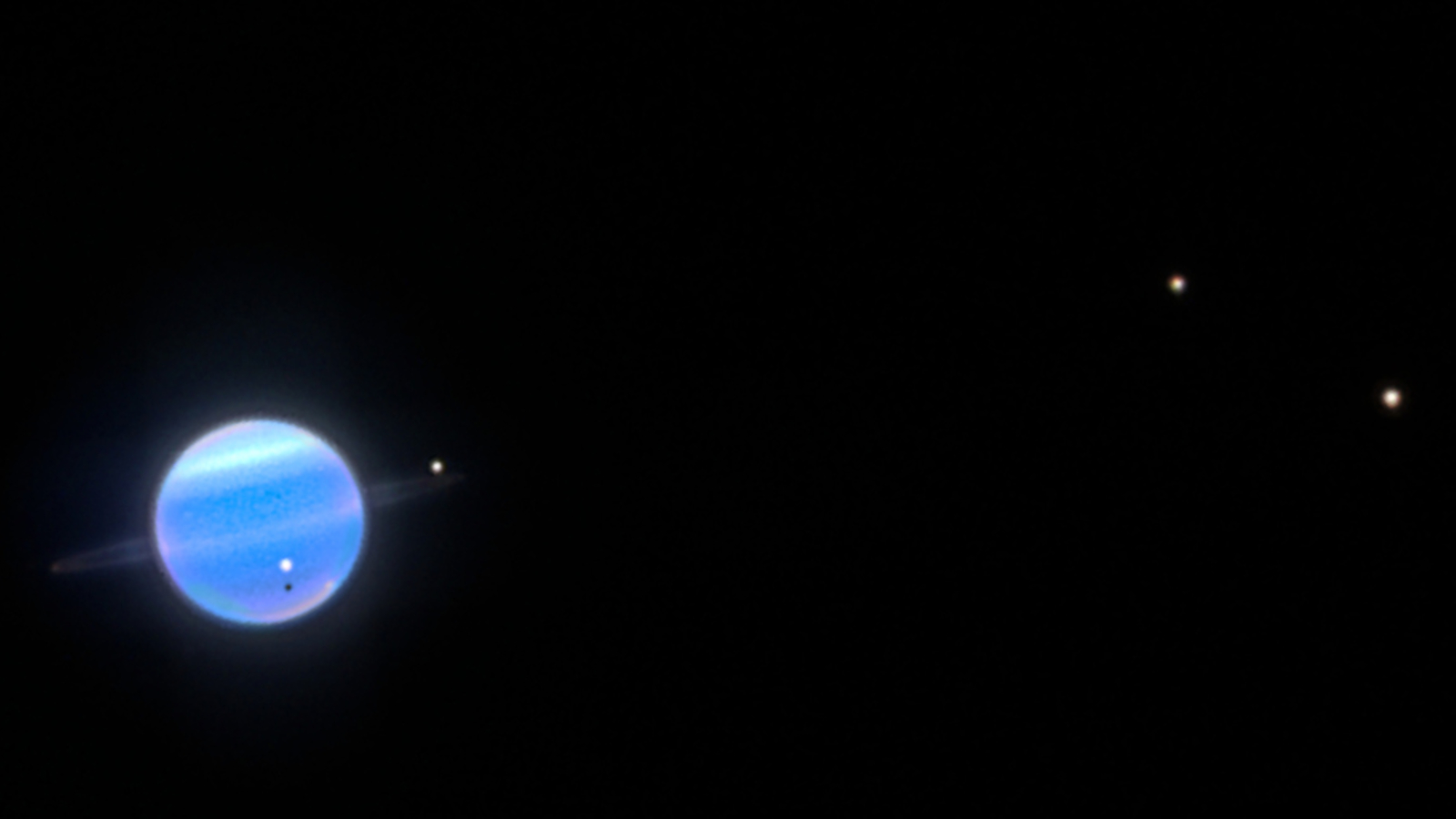

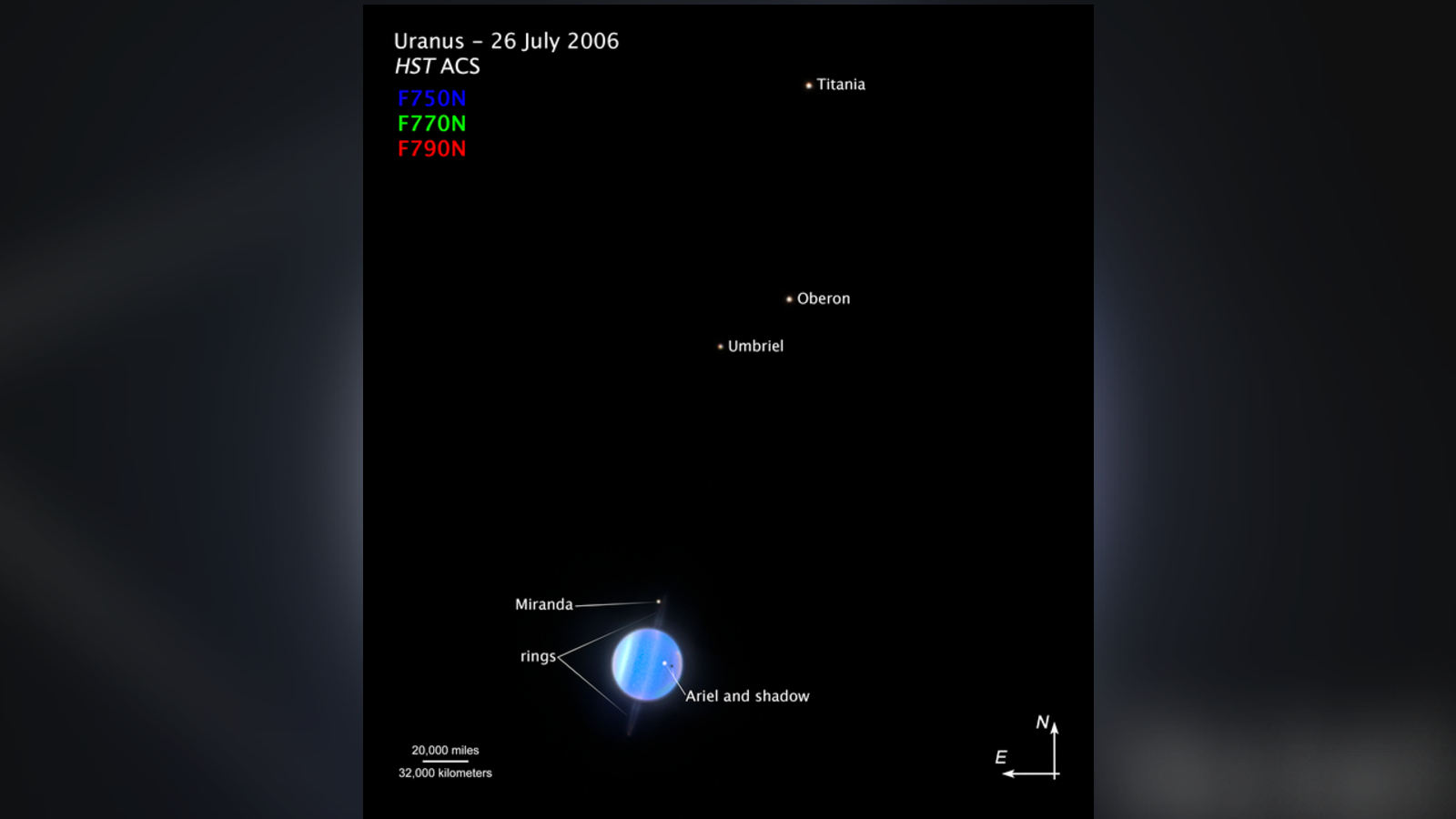

Uranus has 28 confirmed moons, including five major moons. The closest of these large satellites is Miranda, followed by Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon — all named after characters from plays written by William Shakespeare. These icy bodies, which range from 293 to 980 miles (472 to 1,578 kilometers) wide, are all “tidally locked” to Uranus, meaning that the same half of the moon always faces the planet, similar to how Earth’s moon orbits our planet.

Because of this tidal locking, the major moons have a “leading side,” the hemisphere facing forward in their respective orbits, and a “trailing side,” which is always looking back in the satellites’ wake. Scientists had assumed that the leading sides of each moon would be brighter when viewed in invisible wavelengths of electromagnetic light, such as ultraviolet and infrared. This is because electrons from the planet’s magnetic field, or magnetosphere, should be captured by the moons and naturally accumulate on their trailing sides, scattering radiation and making them appear “darker,” similar to some other moons in the solar system.

But in a new study, researchers turned the ultraviolet instruments of the Hubble Space Telescope toward Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon to measure their brightness. Surprisingly, none of the moons’ leading sides were brighter than their respective trailing sides, and on Titania and Oberon, the trailing side was brighter than the leading side, flipping the current theory on its head.

The team shared their findings on Tuesday (June 10) at the 246th American Astronomical Society meeting in Anchorage, Alaska. The results have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Related: Scientists finally know how long a day on Uranus is

While the new findings were a shock, they can be partially attributed to confusion around the magnetic properties of the solar system’s seventh planet. “Uranus is weird, so it’s always been uncertain how much the magnetic field actually interacts with its satellites,” Richard Cartwright, a planetary scientist at the John Hopkins University in Maryland and principal investigator of the study team, said in a statement.

Most of this confusion comes from Uranus’ unusual tilt. The planet’s axis is tilted 98 degrees relative to its orbit around the sun — giving it the appearance of a rolling ball, rather than a spinning top — but its satellites still orbit around its equator, meaning they pass through the magnetosphere at a 59-degree angle. Recent findings also hint that scientists’ current assumptions about the magnetosphere’s size and strength may be wrong, due to magnetic anomalies that occurred 40 years ago when the Voyager 2 probe took the first up-close measurements of the planet.

The new study does not really help us learn anything about Uranus’ magnetosphere because the lack of electrons could be explained by either a weaker magnetic shield or a much stronger and more chaotic one, the researchers said.

However, the unexpected brightness of Titania’s and Oberon’s trailing sides hint at another unknown phenomenon, which researchers have dubbed “dust shielding.” The idea is that little bits of dust around Uranus, which have accumulated over millions of years of meteor strikes on the Uranian moons, are hitting the moons’ leading sides “like bugs hitting the windshield of your car as you drive down a highway,” researchers said.

“This is some of the first evidence we’re seeing of a similar material exchange among the Uranian satellites,” added co-investigator Bryan Holler, a support scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Maryland that oversees Hubble’s science operations. However, similar exchanges have been observed in the systems of Jupiter and Saturn, he added.

This is not the only surprising discovery made about Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon. Recent findings have also hinted that all four of these major moons could support or have previously supported subterranean oceans, similar to those believed to exist on Europa, Ganymede and Enceladus.

The researchers hope that the mysteries surrounding Uranus’ moons could soon be unraveled by the James Webb Space Telescope, which has already helped uncover many of the planet’s secrets using its state-of-the-art infrared instruments.