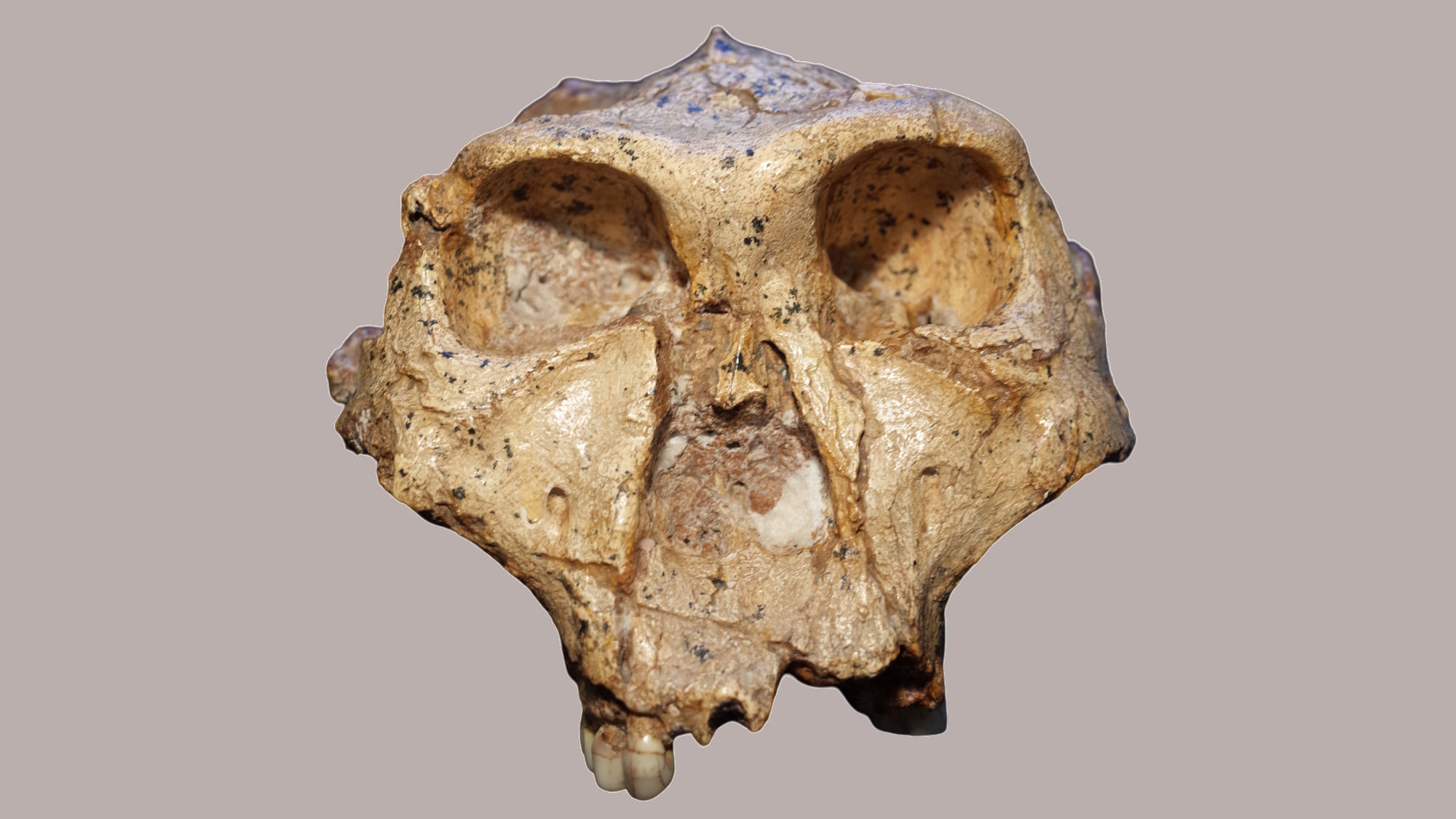

A mysterious type of pitting on the dental enamel of Paranthropus, a genus of extinct human relatives, has baffled experts for decades. But new research suggests the clusters of pits are genetic rather than evidence of a disease, making them key to further understanding the human family tree.

“Teeth preserve an incredible amount of biological and evolutionary information,” study co-author Ian Towle, a researcher in the Palaeodiet Research Lab at Monash University in Australia, told Live Science. “This specific type of pitting might turn out to be a unique marker for certain evolutionary lineages, helping us identify fossils.”

Towle and colleagues detailed their findings in a study published in the July issue of the Journal of Human Evolution. The team revealed that “uniform, circular and shallow” (UCS) pits in the thick enamel of the back molars of Paranthropus relatives is an unusual and interesting pattern.

During growth and development, the enamel layer on the teeth can be disrupted by environmental issues such as malnutrition, leading to defects in the thickness or composition of the enamel. But those defects typically appear as lines or individual pits rather than as UCS clusters.

To better understand which ancient human relatives had UCS pitting, the researchers looked at dozens of teeth from hominins who lived in eastern and southern Africa 3.4 million to 1.1 million years ago. The researchers discovered that the unusual UCS pitting was common across South African sites where Paranthropus lived, and roughly half of the individuals had this type of pitting.

But they found only a handful of instances of possible UCS in other ancient hominin species.

Related: 2.2 million-year-old teeth reveal secrets of human relatives found in a South African cave

For example, in a sample of more than 500 teeth from South African Australopithecus africanus, Towle said that there was no compelling evidence of UCS pitting. This suggests that the Paranthropus hominins found in South Africa did not evolve directly from A. africanus. But East African australopithecines showed some evidence of UCS pitting, suggesting the Paranthropus genus may have evolved from them.

Only a few teeth from individuals in the Homo genus had UCS-type pitting, including H. juluensis and H. floresiensis (the “hobbits”), both hominin species that lived around 200,000 years ago in eastern Asia, the researchers found. The unusual pitting may suggest that these species are more closely related to australopithecines than to other members of the Homo genus, Towle noted in The Conversation.

But with only a few examples in our lineage, it’s currently difficult to draw conclusions about these evolutionary relationships, Towle said. “Further research is essential before UCS pitting can be confidently used as a taxonomic marker in hominin studies” to identify individual species, he said.

One potential way of getting more information from these teeth is through paleoproteomics, the study of ancient proteins trapped in tooth enamel.

“Paleoproteomics could be vitally important for providing further information on UCS pitting and an exciting direction for future research,” Towle said, particularly for investigating whether the pitting is more common among male or female Paranthropus individuals.

Based on the researchers’ work, UCS pitting seems to have been a common genetic trait for millions of years of our Paranthropus relatives’ evolutionary history.

“What we’ve found in our new research is that even tiny surface features like pits or dimples may be useful for understanding hominin biology and ancestry,” Towle said.