Archaeologists in Peru have discovered a 2,500-year-old secret drug room filled with hollowed-out bird bones containing traces of psychedelic snuff and tobacco. The presence of the “snuff tubes” in a hidden room suggests the elite held secret, drug-fueled rituals in pre-Inca times.

“The tubes are analogous to the rolled-up bills that high-rollers snort cocaine through in the movies,” Daniel Contreras, an archaeologist at the University of Florida, told Live Science in an email.

In a study published Monday (May 5) in the journal PNAS, Contreras and a team of archaeologists analyzed the chemical residue in 23 bone and shell artifacts from the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar in the north-central highlands of Peru. They set out to investigate a long-standing assumption that rituals at the site involved psychoactive substances.

This study is the first to show the specific drugs that were inhaled at Chavín, where ritual activity was high but there was little direct evidence of drug use.

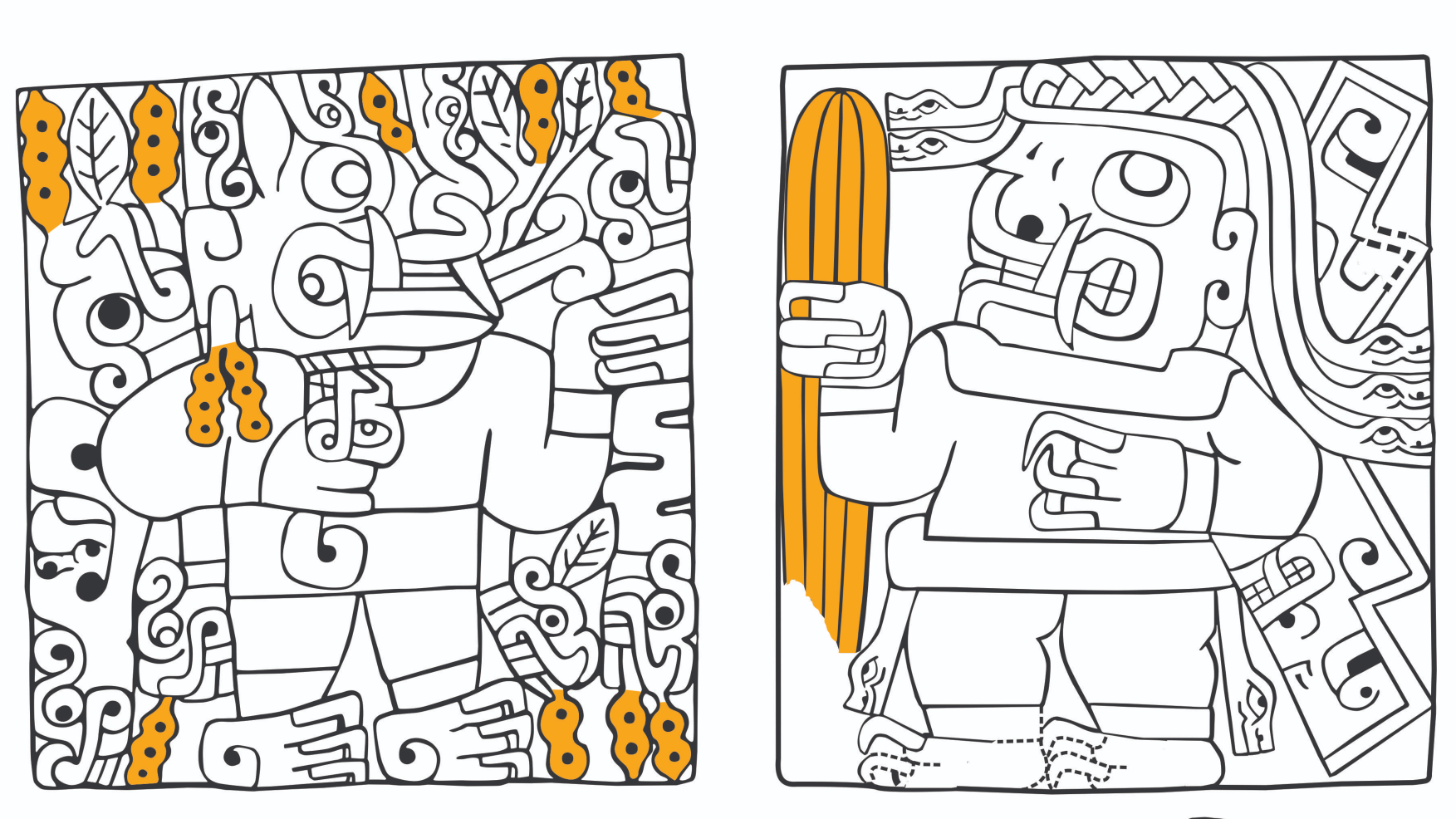

Chavín was a major center of ritual activity between 1200 B.C. and 400 B.C., before the birth of the Inca empire. The complex included stone structures built around open plazas. As people added to the buildings over the centuries, several rooms became interior spaces called galleries.

Related: Secret ancient Andean passageways may have been used in rituals involving psychedelics

One particular gallery was sealed around 500 B.C. and not opened again until archaeological excavation in 2017. When archaeologists explored the gallery, they discovered 23 artifacts carved from animal bone and shell into tubes and spoons.

An analysis of the chemical residue on the artifacts revealed that six contained the organic compounds nicotine, likely from tobacco, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a naturally occurring hallucinogenic drug commonly found in ayahuasca tea.

Further microbotanical analysis showed that four of the artifacts once contained roots of wild Nicotiana species and the DMT-containing seeds and leaves of vilca (Anadenanthera colubrina), which were likely dried, toasted and ground up to produce a potent snuff.

“The tubes would have been used — we think — as inhalers,” Contreras said, “for taking the snuff through the nose.”

The bone snuff tubes, which may have been made from the wings of a peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), were also concentrated in restricted-access areas of Chavín, suggesting that psychoactive substance use was controlled by select participants, the researchers noted in the study.

Because only a handful of people could fit in the small gallery areas at Chavín, the researchers think drug use reinforced the social hierarchy, creating an elite class separate from the workers who built Chavín’s impressive monuments.

“One of the ways that inequality was justified or naturalized was through ideology — through the creation of impressive ceremonial experiences that made people believe this whole project was a good idea,” Contreras said in a statement.

Controlled access to ritual drug use also may help to explain a major social transition in the ancient Andes — from more egalitarian societies to the more hierarchical Tiwanaku, Wari and Inca empires.

These results suggest that additional work is needed to fully understand the importance of psychoactive substances in the ancient Andes, the researchers wrote.