A scientist has discovered the first species of South American scorpion that sprays its venom — a behavior previously only observed in two genera of scorpions found in North America and Africa.

Scorpions are known for their stings — the arachnids, of which there are more than 2,500 known species, use their venom to subdue prey and defend against predators. Their tails terminate in a structure known as a telson, which contains a bulb full of venom. The telson features a pointed aculeus — the stinger — which typically injects the poison.

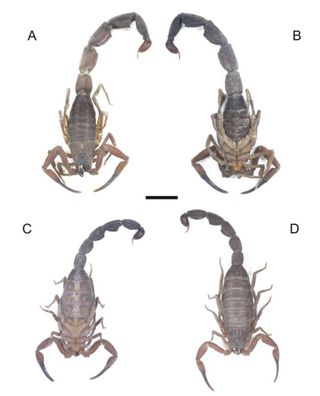

The researcher published his findings Dec. 17, 2024 in a paper in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. The new species, called Tityus achilles, was discovered in the Cundinamarca department of Colombia, in the mountainous Magdelena rainforest region. Only two other genera, found in Africa and North America, have previously been observed spraying venom.

“Most scorpions are likely capable of spraying venom. They just don’t do it. This extreme behavioral response is only known to occur regularly in those two genera,” author Léo Laborieux, who was a masters student at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich at the time of the research, told Live Science.

“Venom-spraying is an inherently expensive strategy,” he added. “There is likely a very intense selection pressure that would make it so that the behavior is more advantageous than it is disadvantageous. There has to be something going on with the predators in the environment.”

Related: We now know why tarantulas are hairy — to stop army ants eating them alive

This technique for delivering toxins has been observed in other organisms — for example, spitting cobras can spray adversaries with venom too. Toxins that are externally applied in this fashion are called toxungens. A wide variety of animals, from arthropods to mollusks to mammals, use toxungens in defense and occasionally for hunting. These compounds may be sprayed, smeared or passively transmitted.

But unlike many other organisms that use toxungens, T. achilles is both poisonous and venomous. Poisonous animals transmit their toxins through external contact or ingestion while venomous animals inject them using their teeth or other specialized organs.

T. achilles can both inject and spray its venom. Direct injection of venom ensures that it is delivered and affects the target. But it comes at a physical risk — the target, whether predator or prey, may in turn defend itself.

Spraying venom is less risky — it does not require direct physical contact. But it is also less targeted and the effects of the venom are less severe. Still, a squirt of toxin to the face may be enough to deter a predator and allow the scorpion to escape. The angle of the toxic spray produced by T. achilles suggests that it may be targeted toward the eyes and nose of its attackers.

“These toxins need to reach very sensitive tissues to actually take effect,” Laborieux said. “For this to make sense, the predator has to be a vertebrate.” The toxins would be unlikely to penetrate the exoskeleton of another invertebrate, he noted, suggesting that the technique would be useless in securing prey.

Laborieux tested the ability of T. achilles to spray its venom by pinning specimens down with a drinking straw and recording their reactions. He tested 10 juvenile scorpions and recorded 46 ejections of venom, which reached a maximum distance of 14 inches (36 centimeters).

In some cases, the scorpions flicked small droplets of venom in response to the straw. In others, they issued a sustained spray. Most of the pulses of venom were directed forward, though some were also directed backward or upward.

The majority of venom flicks and sprays were transparent, suggesting that they consisted of pre-venom, a toxic liquid that is typically ejected prior to more potent true venom, which has a milky tint.

“The venom itself is usually composed of higher molecular weight peptides and proteins which are much larger, and for that reason, much more expensive to produce,” Laborieux said.

A quick spray of pre-venom as a defense mechanism is thus a more conservative measure for a small organism that also uses these same compounds to subdue its prey — and will likely encounter additional predators in short order.