QUICK FACTS

Milestone: The first two-way phone call across outdoor lines

Date: Oct. 9, 1876

Where: Cambridgeport to Boston, Massachusetts

Who: Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Watson

On the afternoon of Oct. 9, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was in Boston when he had a three-hour chat with his assistant and fellow inventor, Thomas Watson. It would not have been noteworthy — except that Watson was across the Charles River, in Cambridgeport.

Bell and Watson had spoken via their device as early as March of that year, soon after Bell’s improved “telegraphy” device was patented. But the crackly command — “Mr. Watson, come here; I want to see you,” was issued over only a short distance.

In contrast, the call that October day lasted a few hours and was transmitted via long telegraph wires.

Bell was in a crowded field of inventors who were dreaming up new ways to transmit sound via electricity. A few decades earlier, Antonio Meucci created — and took preliminary steps to patent — a “telectrophone” to communicate with his bedridden wife in another room. In 1861, German inventor Johann Philipp Reiss coined the term “telephon” to describe a device of his own, which converted sound waves to an electrical signal and back. His transmissions faithfully reproduced melodies, but words were too garbled to be understood. And around the same time as Bell, Elisha Gray developed a similar water-microphone-based design.

Key to Bell’s ability to transmit a voice was the notion of transmitting multiple frequencies simultaneously, which he did by using what he called an “undulatory” — or variable — current, rather than the pulses of intermittent current that Samuel Morse had used for his telegraph.

“The rate of oscillation in the electrical current corresponds to the rate of vibration of the inducing body — that is, to the pitch of the sound produced,” Bell’s patent states. “The intensity of the current varies with the amplitude of the vibration — that is, with the loudness of the sound.” In short, the features of the current encode features of the sound.

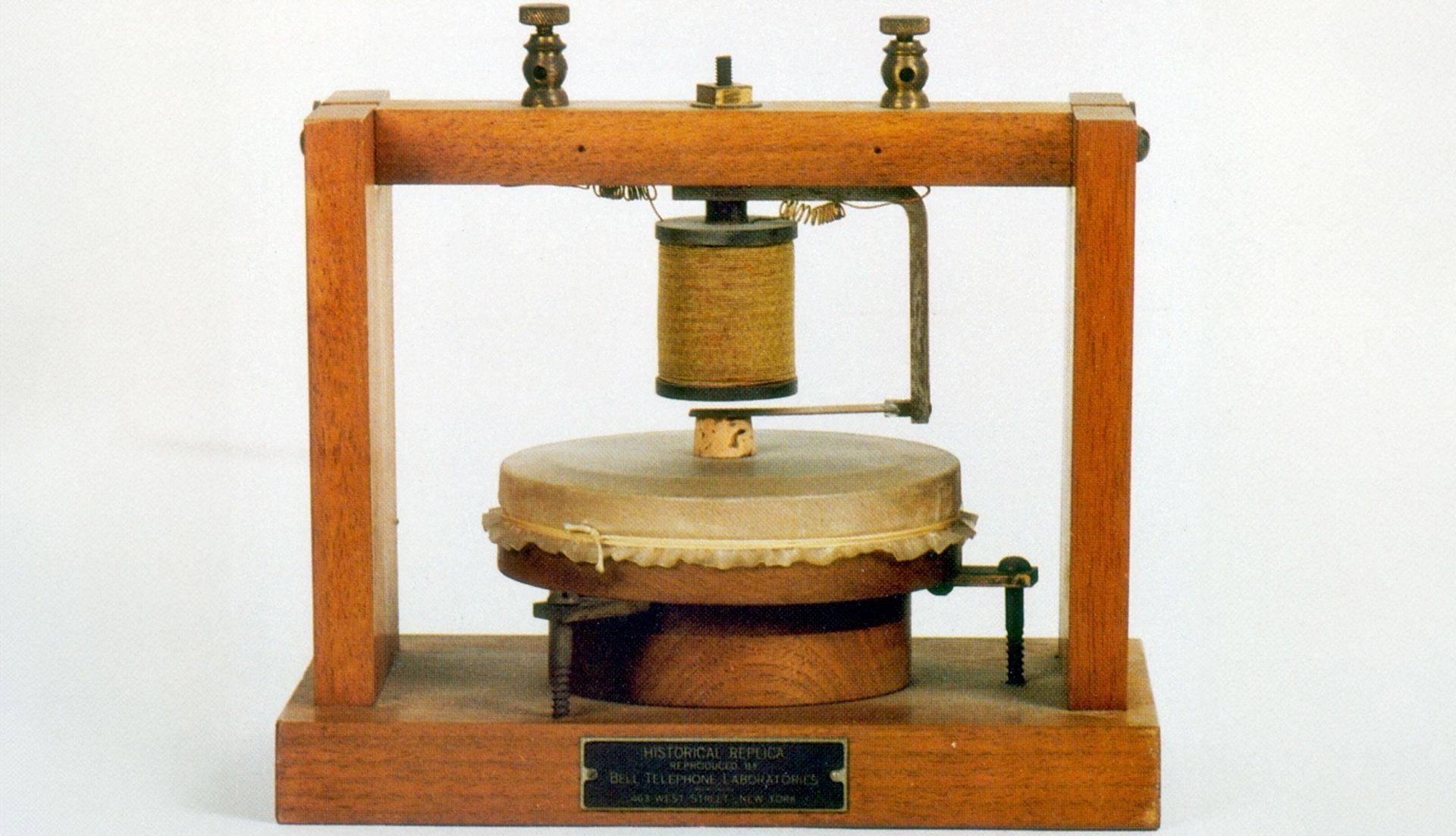

Bell’s first prototype used a diaphragm, an inductor (an iron core encircled by a coil of wires), a permanent magnet, and connecting wires. When a sound wave hit the diaphragm, the pressure waves caused that diaphragm to vibrate. These vibrations moved the inductor, altering the magnetic field it produced, which, in turn, caused current to flow in the coiled wire. That current was then transmitted via wires to the receiver, which had the same elements in reverse.

That first long-distance conversation was galvanizing, but the first telephone line, which was laid in April 1877, only connected a merchant’s shop with his home. Phone lines were initially rented in pairs and were used to connect discrete locations. But the opening of “central exchanges” and switchboards around a year later enabled calls to be routed between locations, dramatically improving the usefulness of the invention.

It would be decades before the first transcontinental and cross-continental calls were made, and the first undersea trans-Atlantic phone cables were laid in 1956.

The telephone industry helped spur a number of other modern innovations, including switches, the transistor that would usher in the computing era, fiber-optic cables for data transmission, and communications satellites.