An astrophysicist has made an ambitious proposal for how humanity could probe the extreme physics of black holes — by sending a spaceship no bigger than a paperclip to our nearest one.

The spacecraft, no heavier than a gram and propelled to a third of the speed of light by lasers on Earth, would gather information on a nearby space-time rupture within the next century, according to the plan.

Published August 7 in the journal iScience, the blueprint made by the astrophysicist Cosimo Bambi at Fudan University in Shanghai, China contains a lot of what ifs: Most crucially, it’s based on technology that doesn’t yet exist, and relies on finding a black hole close enough to Earth (which hasn’t happened yet). Yet Bambi insists that it’s still worth planning for.

“It may sound really crazy, and in a sense closer to science fiction,” he said in a statement. “But people said we’d never detect gravitational waves because they’re too weak. We did — 100 years later. People thought we’d never observe the shadows of black holes. Now, 50 years later, we have images of two.”

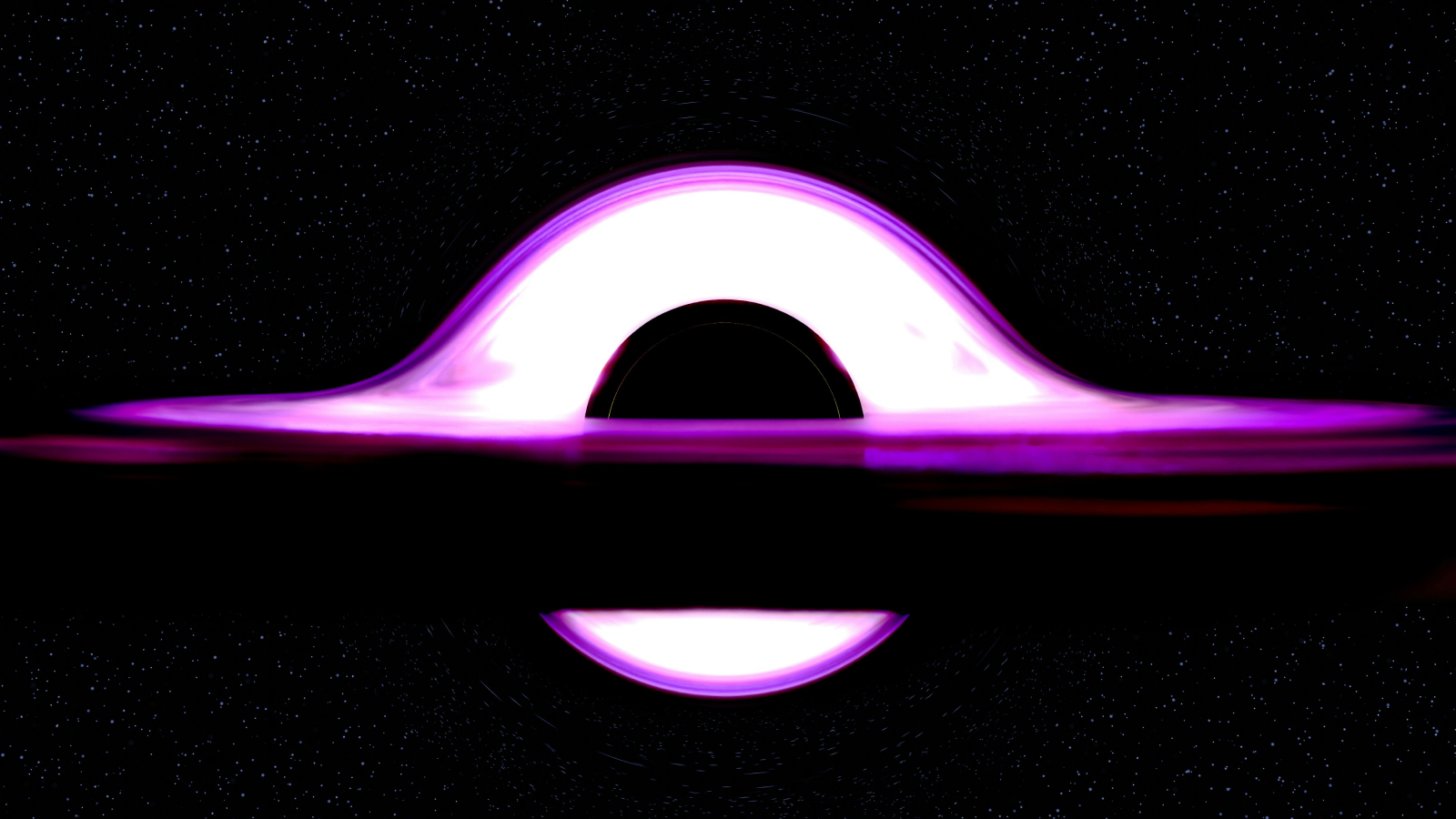

Related: See the universe’s rarest type of black hole slurp up a star in stunning animation

Black holes are born from the collapse of giant stars and grow by ceaselessly gorging on gas, dust, stars and other other black holes in the star-forming galaxies that contain them.

The space-time ruptures are regions of space where the equations of Einstein’s general theory of relativity (which describe how gravity works) break down, making them exciting targets of study for scientists looking for a unified theory of gravity and particle physics.

But sending a spacecraft to a black hole would first require finding one close enough to us. Currently, the nearest black hole to our planet is 1,500 light years away, far too great a distance for humanity to feasibly send a craft to.

In fact, any black hole sitting beyond 50 light-years distance will likely render Bambi’s mission impossible, but he points to new gravitational microlensing techniques that are making the discovery of smaller, nearby black holes possible. If one is found closer, ideally within 25 light-years of us, it could become a target.

“There have been new techniques to discover black holes,” says Bambi. “I think it’s reasonable to expect we could find a nearby one within the next decade.”

If we do find a black hole that’s close enough, the next challenge is getting there. For that, Bambi proposes the development of a nanocraft sporting a 108 square foot (10 square meter)-solar sail, propelled to 224 million mph (360 million km/h) from a blast of high-powered laser light to close the distance in roughly 70 years.

Once there, the nanocraft would release a probe to approach the black hole while it remains in orbit, beaming the collected data back to Earth. Bambi stresses that today the laser power alone would likely cost more than a trillion dollars, but that costs could decrease as technology improves.

“We don’t have the technology now,” he said. “But in 20 or 30 years, we might.”