For the first time, scientists have captured a real-time view of a human embryo implanting in a laboratory model of a uterus.

Being able to witness the complex implantation process may be helpful for advancing fertility procedures, such as in vitro fertilization (IVF), the researchers say.

“We have observed that human embryos burrow into the uterus, exerting considerable force during the process,” study co-author Samuel Ojosnegros, principal investigator for the Bioengineering for Reproductive Health Group at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) in Spain, said in a statement. “It is a surprisingly invasive process.”

In a study published Friday (Aug. 15) in the journal Science Advances, the researchers detailed their invention of an apparatus that enabled them to record a video showing how human embryos implant. The process let them measure the force exerted during implantation and see how it differs between human and mouse embryos.

During implantation, mammalian embryos attach to the endometrium — the lining of the uterus — and then begin to develop and give rise to more and more cells. Sometimes, though, this biological process doesn’t work as expected. “Implantation failure is one of the main causes of infertility, accounting for 60% of miscarriages,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Studying how embryo implantation works in humans is difficult in part because it requires capturing a short moment in time inside a complex organ. Capturing that fleeting moment would be especially difficult inside a person — for instance, a patient undergoing IVF — given that it could be risky to disrupt the reproductive system at that time.

Related: Should we rethink our legal definition of a human embryo?

As such, the only footage of human implantation captured before the new study was a series of still images of embryos at specific moments in the process and in a simple laboratory model of the uterine environment.

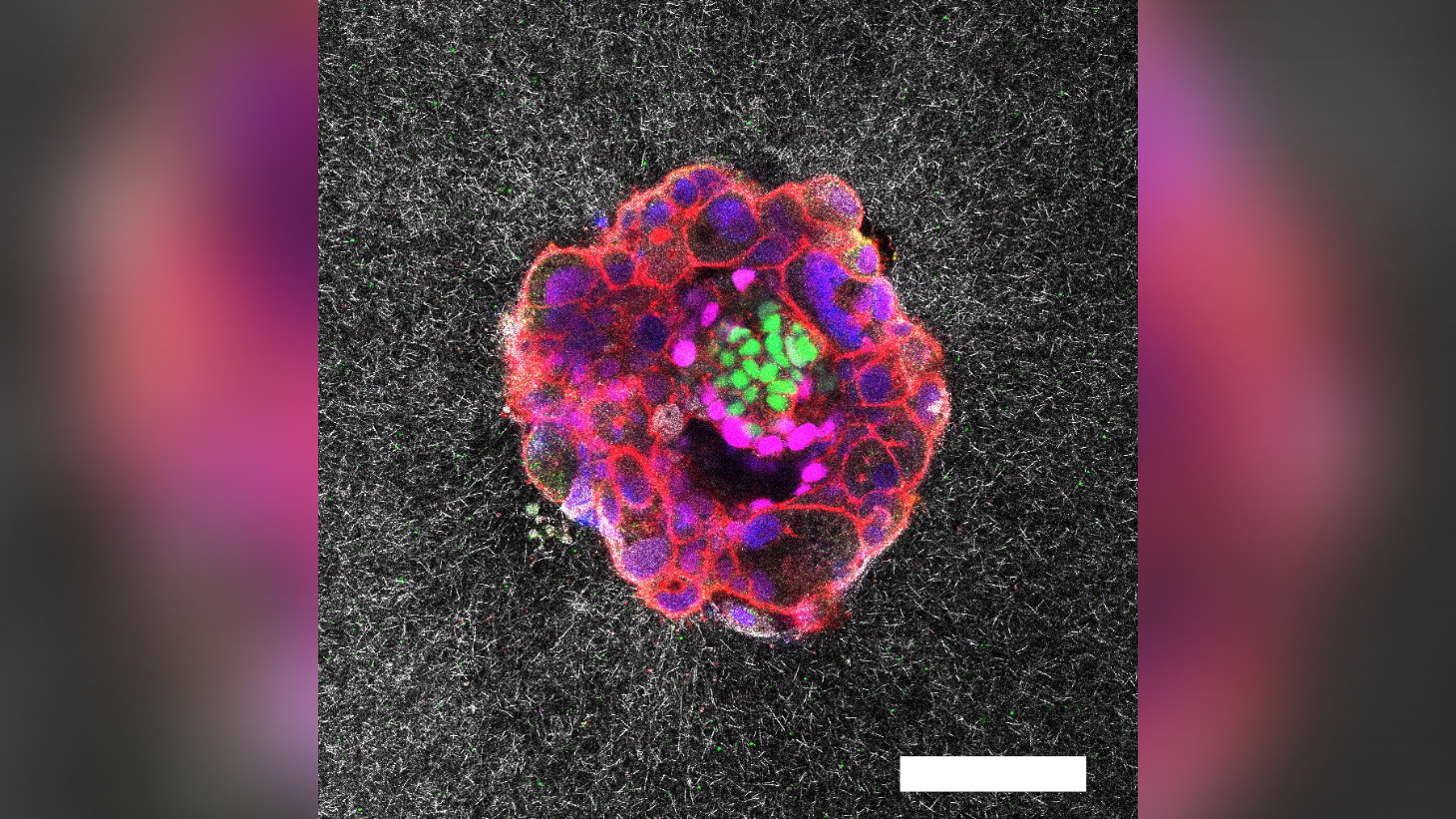

Now, researchers at IBEC have developed a way to capture the implantation of a human embryo in four dimensions. First, they created a gel made of various proteins in uterine tissue, including collagen, and put early-stage embryos in the gel. The embryos used in this study were donated by couples undergoing IVF.

This setup enabled the team to use microscopy and fluorescence imaging techniques to record the embryos’ implantation into the gel. When watching the implantations, they discovered that, after releasing enzymes that broke down the uterine tissue, the human embryo invaded the uterus.

“The embryo opens a path through this structure and begins to form specialised tissues that connect to the mother’s blood vessels in order to feed,” Ojosnegros said. (Research done by other labs has detailed how the placenta — the temporary organ that supplies oxygen and nutrients to the fetus — similarly invades a major maternal artery in order to form in early pregnancy.)

They also found that the burrowing embryo exerted force on the uterus, essentially moving and reorganizing the tissues. The embryos also appeared to respond to external forces that they encountered, such as the addition of other cells and structures into the goo. “We hypothesize that contractions occurring in vivo [in the body] may influence embryo implantation,” study co-author Amélie Godeau, a researcher at IBEC, said in the statement.

These contractions may hold one key to successful implantation, the researchers suggested in the study. The human uterus spontaneously contracts one to two times per minute, on average, and the nature of these contractions changes throughout the menstrual cycle. A previous study found that people with too many or too few uterine contractions on the day of embryo transfer in IVF had lower implantation rates than people with a “just right” amount.

“This suggests that there may be an optimal frequency range favorable for embryo implantation,” the researchers wrote. The exact role of uterine contractions in successful implantation is still being studied, though.

A better understanding of the complexity of the human uterus and the process of implantation may lead to better IVF outcomes in the future, the study authors proposed.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.