Before weight coach Bella Barnes consults with new clients, she already knows what they’ll say. The women struggle with their weight, naturally. But they don’t want to lose pounds. They want to gain them.

Her clients find themselves too thin, and they’re suffering. “Last week, I signed up a client who wears leggings that have bum pads in them,” says Barnes, who lives in Great Britain. “I’ve had another client recently that, in summer, wears three pairs of leggings just to try and make herself look a bit bigger.”

These women belong to a demographic group that has been widely overlooked. As the world focuses on its billion-plus obese citizens, there remain people at the other end of the spectrum who are skinny, often painfully so, but don’t want to be. Researchers estimate that around 1.9 percent of the population are “constitutionally thin,” with 6.5 million of these people in the United States alone.

Constitutionally thin individuals often eat as much as their peers and don’t exercise hard. Yet their body mass index is below 18.5 — and sometimes as low as 14, which translates to 72 pounds on a five-foot frame — and they don’t easily gain weight. The condition is “a real enigma,” write the authors of a recent paper in the Annual Review of Nutrition. Constitutional thinness, they say, challenges “basic dogmatic knowledge about energy balance and metabolism.” It is also understudied: Fewer than 50 clinical studies have looked at constitutionally thin people, compared with thousands on unwanted weight gain.

Recently, researchers have started to investigate how naturally thin bodies are different. The scientists hope to unlock metabolic insights that will help constitutionally thin people gain weight. The work may also help overweight people lose pounds, since constitutional thinness appears to be “a mirror model” of obesity, says Mélina Bailly, a coauthor of the recent review and a physiological researcher at AME2P, a metabolism research lab at the University Clermont Auvergne in France.

Individuals who eat heartily but remain inexplicably skinny were first reported in the scientific literature in 1933. Decades later, a landmark 1990 experiment demonstrated how profoundly people differ in regulating their weight.

Twelve pairs of identical twins were fed 1,000 surplus calories for six days a week. After three months of such overfeeding — equivalent to an extra Big Mac and medium fries daily — the young men had gained an average of almost 18 pounds, mostly fat, but within a large range: One gained almost 30 pounds and another fewer than 10. The latter had somehow diffused around 60 percent of the extra energy.

The study also found that the variation of weight gain was three times greater between twin pairs than within them — indicating a genetic influence on the tendency to add pounds when overfed.

Other studies confirmed that constitutionally thin people largely “resist” weight gain, particularly when eating fatty foods. Whatever pounds they do gain through overfeeding rapidly vanish once they resume normal eating.

After bouts of overfeeding, bodies generally shed weight. But as this graph illustrates, there is variability in both responses to overfeeding and in the return to a body’s “normal” weight. (“Ad libitum” refers to a period in the experiment when participants eat what they want.)

This aligns with current thinking to some extent. Many researchers believe that our bodies have a preprogrammed weight “set point” or “set range” to which they try to return. That’s one reason few dieters manage to keep off lost weight long-term. Their metabolism slows down, burning fewer calories and making weight regain easier, particularly once the dieter stops restricting calories. (The system displays some flexibility, explaining why many of us put on inches around our midsections over the years.)

‘Skinny shaming’

As a group, lean individuals are probably as heterogeneous as overweight people. Some may stay thin because they have smaller appetites or feel full sooner. Others consume just as many calories as heavier individuals. One study found that constitutionally thin people eat 300-plus calories more per day than their metabolism needs. “They have a positive energy balance and they still resist weight gain,” says Bailly, a collaborator on NUTRILEAN, a project focused on constitutional thinness, at University Clermont Auvergne in France.

Like obese people, constitutionally thin people face their social stigma. Thin men may feel too scrawny to satisfy masculine ideals. Skinny women often lament lacking curves. People might suspect they are hiding eating disorders. They get “comments from random people on the street,” says Jens Lund, a postdoc in metabolic research at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen. “These people feel like they can’t go to toilet after a family dinner … because they are afraid that people would look at them as if they’re going out to puke, like having bulimia.”

Weight gain coach Barnes was never technically all the way in the constitutionally thin category, but she experienced plenty of such “skinny shaming” firsthand. Family members commented on her weight but dismissed her distress. “I felt like I could never speak about it,” she says. “People would be like, ‘That’s not a real problem,’ or ‘Just take some weight from me.'”

Where do the calories in constitutionally thin people go? Researchers have started eliminating possibilities.

Researchers are learning that there are large individual differences in how the body uses up calories. (Thermogenesis is the metabolic process in which calories are burned to generate heat.)

A 2021 meta-analysis offered some surprises. When Bailly and colleagues compiled data on thin people’s body composition, they discovered something unexpected: Constitutionally thin individuals carry nearly normal amounts of fat throughout their bodies. “It’s really unusual to have such low body weight combined with quite normal fat mass,” says Bailly.

What seems to be lacking is muscle mass. Constitutionally thin people have less of it — research has found that they have muscle fibers that are on average about 20 percent smaller than those of normal-weight people. Constitutionally thin people may also have reduced bone mass.

These facts suggest that there are health costs to leanness. Though studies are lacking, Bailly suspects that as they age, especially thin women might run a higher risk of osteoporosis, a dangerous weakening of the bones. The reduced muscle mass could also make everyday tasks, like opening jars or carrying groceries, more arduous.

And it could mean fewer protein reserves during illness, says Julien Verney, a physiological researcher at Clermont Auvergne’s metabolic lab and coauthor of the Annual Review of Nutrition paper.

In addition to body composition differences, researchers speculate that constitutionally thin bodies “waste” calories. For example, some studies suggest that while thin individuals exercise less, they fidget more.

They may also excrete more calories than others. While this hasn’t been explored specifically for lean people, it’s known that some people lose up to 10 percent of ingested calories through feces (and to a lesser extent, urine), compared to just 2 percent in others. In one study, a woman excreted 200 calories daily — equivalent to half a liter of soda.

Additional metabolic idiosyncrasies of constitutionally thin people may still await discovery. “We recently found some clues that may suggest more metabolic activity of their fat mass tissues,” says Bailly. “This is really surprising.” Other studies have already suggested that naturally thin people have more “brown fat” — a calorie-burning tissue that generates body heat.

To find more specific answers, Lund plans to launch an inpatient study at the University of Copenhagen. The study will use a metabolic chamber to track energy intake, expenditure and all routes of energy loss — including feces, urine and exhaled gases — in constitutionally thin people. Since 2020, Lund’s team has assembled a network of Danes who self-report as naturally lean, providing a unique pool for future research.

Constitutional thinness, as the 1990 twin study showed, has a strong genetic component: Research shows that 74 percent of very lean people have relatives with similar stature. As researchers identify gene variants, they realize that many of these — with names like FTO, MC4R and FAIM2 — are also involved in processes leading to obesity. Although they don’t yet understand the specifics, scientists suspect that people with constitutional thinness may have unique activity patterns in genes related to energy production.

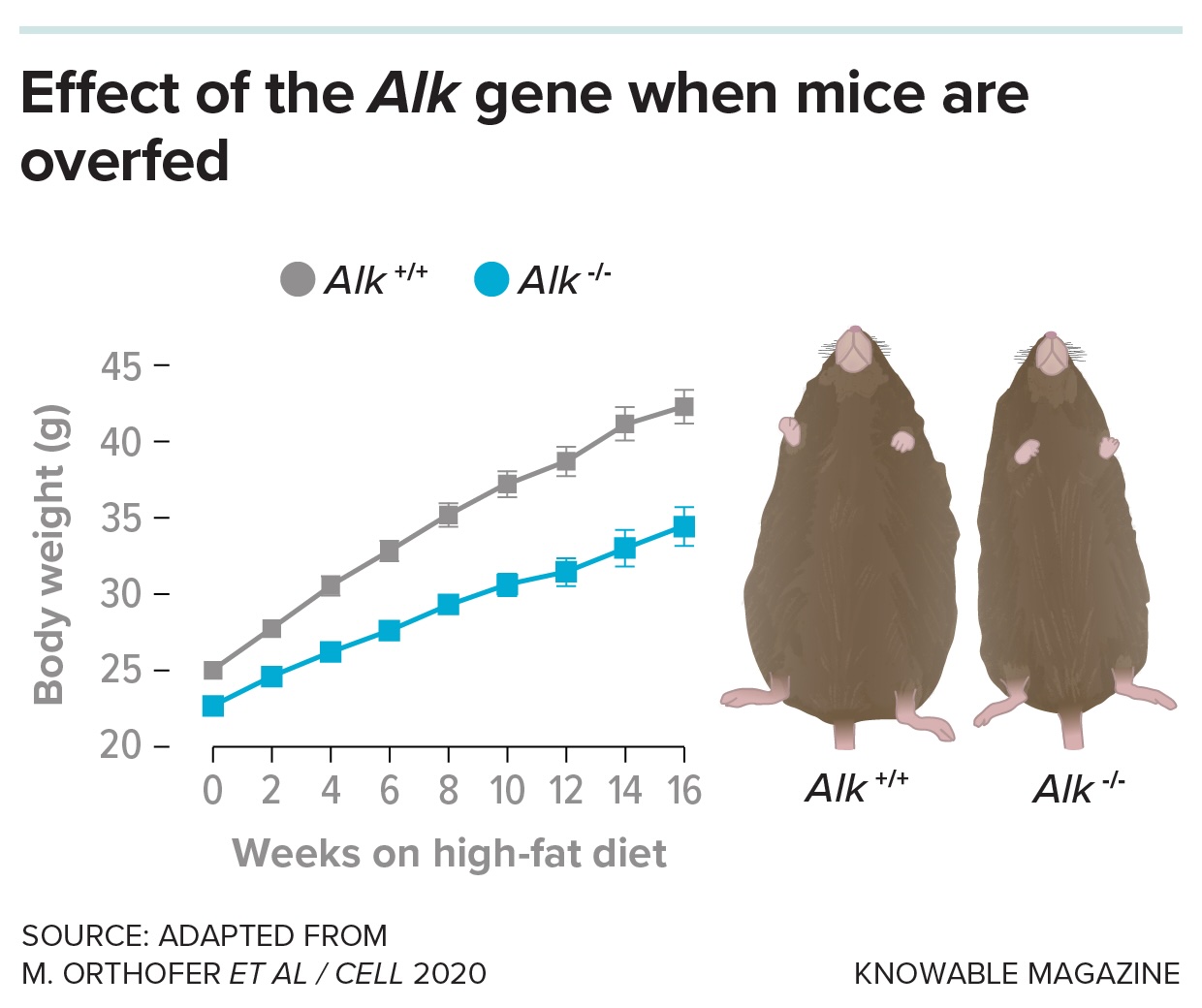

One such gene that has drawn researchers’ attention is ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase). When scientists deleted this gene in mice, the animals became resistant to weight gain when fed high-fat diets — even in mouse strains genetically prone to obesity. The ALK gene seems to act in the brain, which then sends signals affecting the rate at which fat cells burn energy.

Understanding genetic mechanisms like these could lead to new treatments for both unhappily thin and unhappily obese people, says Lund. “If you can figure out what protects them from developing overweight, then whatever that mechanism is, you can then try to turn that into a drug,” he says. “There are so many signaling molecules in the body that we don’t even know exist.” The dream is to find a breakthrough as transformative as the latest obesity medications.

While researchers hunt for biological clues, Bella Barnes navigates the complexities of weight gain on her own. After years of trial and error, she gradually gained about 40 pounds by combining strength training with careful, intentional eating. At first, if she hadn’t reached her calories for the day, she’d just grab a packet of cookies — anything to get the numbers up. But she found more balance over time. “Not all calories are the same. You want to be eating whole foods,” she says. And a lot of them.

Today, Barnes has coached more than a hundred women on her weight gain techniques and has a strong TikTok following; she says that she’s proud of the strong body she’s built.

Maybe five more pounds, she adds, “would make me at my happiest.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.