Caffeine may help some bacteria keep antibiotics out of their cells, potentially reducing the therapeutic effects of the drugs, a new laboratory study hints.

However, experts caution that it’s not yet clear how this effect might play out in humans, so caffeine drinkers needn’t panic yet.

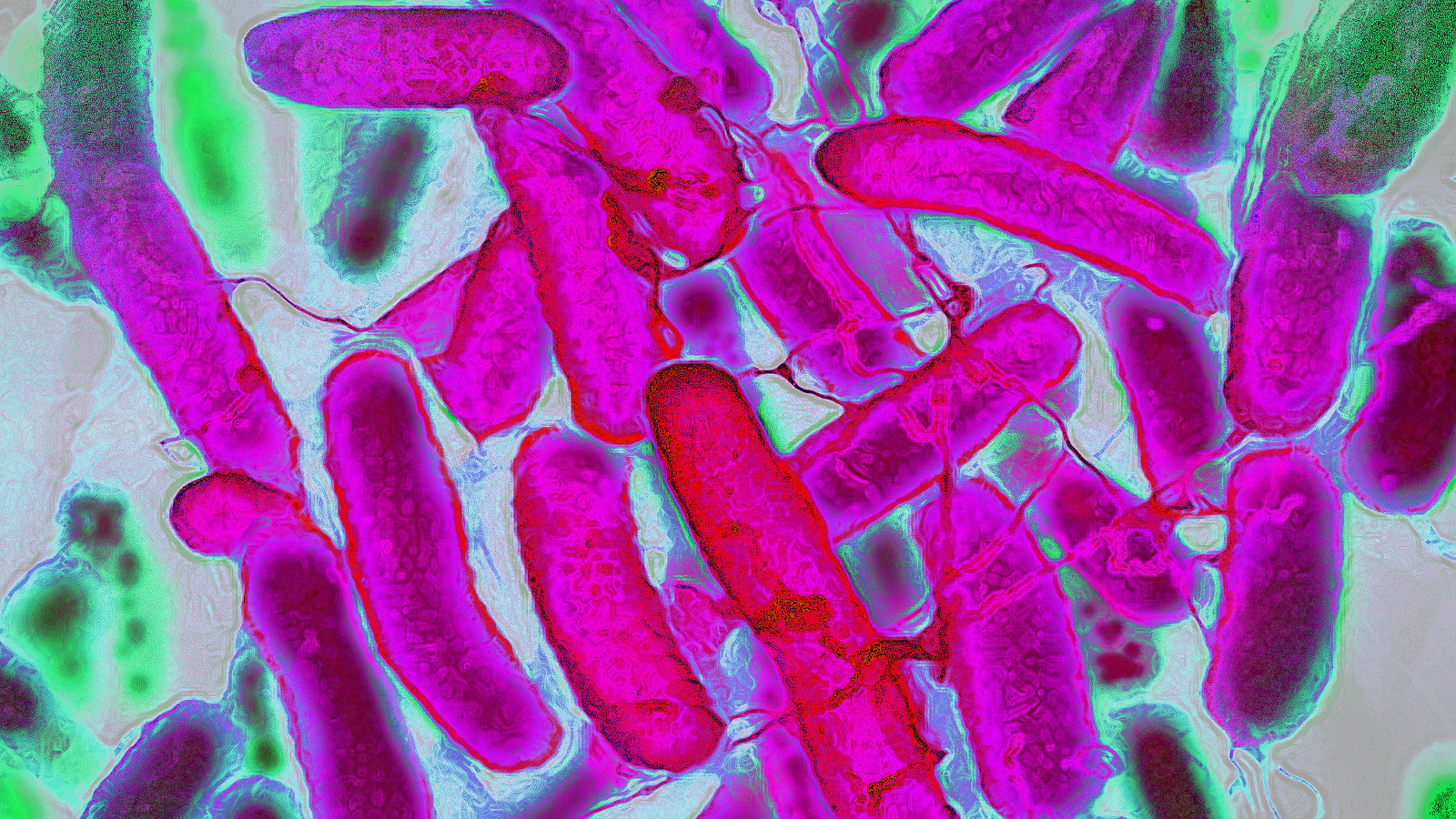

Scientists have known for decades that bacteria can protect themselves by pumping out harmful substances through special transport proteins in their outer layers — and this ability helps bacteria resist the effects of drugs that would otherwise kill them. However, it wasn’t clear how bacteria change the activity of the genes behind these transport proteins in response to molecules they encounter.

To learn more, researchers tested how the common gut bacterium Escherichia coli — better known as E. coli — responded to 94 different chemical compounds, including antibiotics and aspirin, as well as products made in the gut, like secondary bile acids. They also looked at small molecules found in common foods, such as vanillin, the compound that gives vanilla its flavor, and caffeine.

Their study, published July 22 in the journal PLOS Biology, showed that many different chemicals can trigger changes in bacterial transport-related genes and thus potentially affect their response to antibiotics.

Related: Superbugs are on the rise. How can we prevent antibiotics from becoming obsolete?

For example, caffeine was found to reduce the production of a transport protein called OmpF, which helps bring common antibiotics — like ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin — into bacterial cells’ membranes or innards. In theory, with fewer of these OmpF proteins available, the antibiotics cannot access their targets within the cells as easily, making them less effective.

But this finding shouldn’t worry coffee drinkers just yet — there are many potential variables that haven’t been studied yet, said April Hayes, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Exeter who was not involved in the study. “This would include whether the effect of caffeine would reduce the body’s ability to clear infections,” Hayes told Live Science.

Andrew Edwards, a professor of molecular microbiology at Imperial College London, agreed that “there’s no evidence from this study that drinking coffee will affect a person’s response to antibiotics and nobody should change their routine.” Edwards, who was not involved in the study, said he recommends that people prescribed antibiotics follow their doctor’s guidance and the instructions that come with the medicine.

Adaptable microbes

In the study, researchers at the University of Tübingen in Germany looked at how seven genes involved in transport inside E. coli responded to different chemicals. Out of the 94 substances they tested, 28 changed the activity of these genes.

The chemicals that had an effect included caffeine; the weed killer paraquat; and certain classes of antibiotics, like tetracyclines and macrolides. Drugs that block folic acid, which are used to treat some cancers and inflammatory diseases, and salicylates, a broad class of drugs that includes aspirin, also had an effect.

“This study adds to a growing appreciation that bacteria can sense and respond to numerous different stimuli … all of which can affect the susceptibility of the microbe to antibiotics,” Edwards said.

One-third of the chemical-induced genetic changes involved the Right-origin-binding protein (“Rob,” for short), which switches genes on or off by binding to specific DNA sequences. The findings suggest that Rob plays a bigger role in helping E. coli adapt to its environment than previously thought.

For now, though, it’s still unclear exactly how caffeine changes gene activity in E. coli or interacts with Rob at the molecular level. Additionally, the researchers don’t yet know whether the effects seen in lab experiments happen the same way during real infections in people.

In the study, the researchers found that caffeine’s ability to interfere with how antibiotics work also applied to a strain of E. coli sampled from a real patient with a urinary tract infection. This lab experiment suggests the effect of caffeine on bacteria could have important implications for human health — but again, that will need to be confirmed in future research.

Future research could also look at microbes beyond E. coli. The researchers suspect their findings may also have implications for how other bacteria tweak their transporters over time.

But importantly, “at this point, it still seems highly unlikely that consuming caffeine would result in a difficult-to-treat infection,” Hayes said. “Overall, this study is interesting, but is not a cause for concern for caffeine consumers.”

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical or dietary advice.