A toxic fungus, once thought to have caused fatal lung infections in tomb explorers, may hold the key to powerful new cancer treatments, new research suggests.

Within months of the discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922, the earl who had financed the excavation and visited the “wonderful” burial site died, leading many to believe the mummy had cursed those who entered the tomb. In the 1970s, 10 of the 12 archaeologists excavating the 15th-century crypt of King Casimir IV in Poland also met a similar fate.

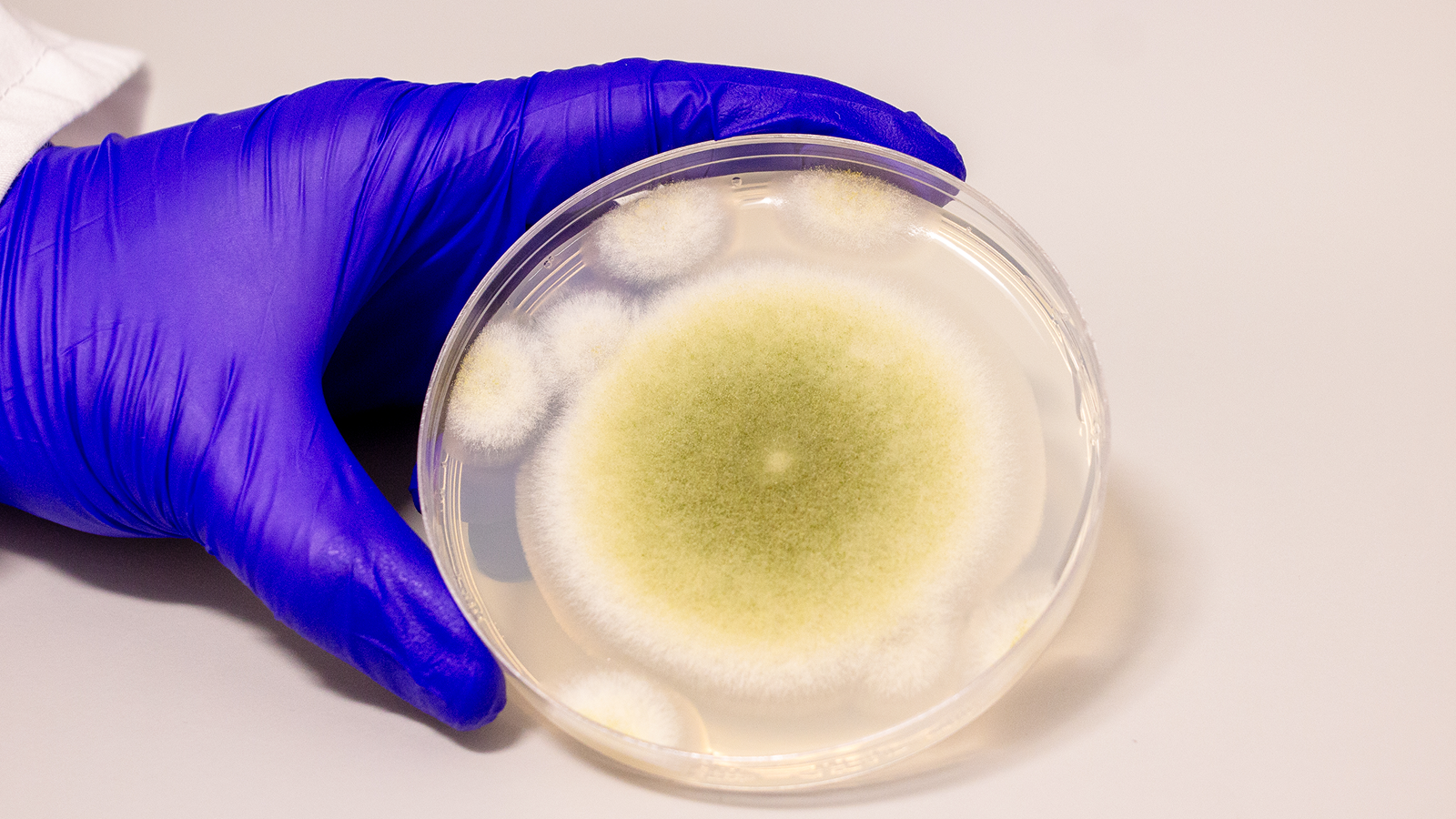

Analysis of Casimir’s tomb revealed the presence of a fungus called Aspergillus flavus, the toxins of which are known to cause a deadly lung infection.

Now, the same fungus has shown promise as a treatment for leukaemia, according to a new study published in Nature Chemical Biology. The researcher team identified and engineered a class of molecules within the fungus, called asperigimycins, that kill leukemia cells in a laboratory setting.

“This is nature’s irony at its finest,” study senior author Sherry Gao, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, said in a statement. “The same fungus once feared for bringing death may now help save lives.”

Aspergillus flavus produces spores that are able to lie dormant for centuries — including inside sealed tombs. When disturbed, the fungus can cause deadly respiratory infections, particularly in people with weakened immune systems.

Related: College student discovers psychedelic fungus that eluded LSD inventor

In their new study, the scientists examined the unique chemical compounds produced by the fungus and discovered a class of natural compounds called RiPPs (ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides). These molecules are difficult to isolate and rarely seen in fungi, but they hold therapeutic promise due to their complex structures and bioactivity. This means they have intricate, unique shapes that can interact with biological systems in powerful ways, such as killing cancer cells.

“We found four novel asperigimycins with an unusual interlocking ring structure,” lead author Qiuyue Nie, a researcher in chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, said in the statement. “Two of them had strong anti-leukemia properties even without modification.”

To enhance the drugs’ effectiveness, the researchers attached lipid molecules similar to those found in royal jelly, the nutrient-rich substance that sustains queen bees. This enabled the drugs to enter cancer cells more efficiently, because lipids help drugs cross cellular membranes, which are made largely of fats themselves.

Further analysis revealed how a gene called SLC46A3 acts as a kind of molecular gateway, helping the drug escape cellular compartments and target leukemia cells directly. This discovery could aid in the delivery of other promising but hard-to-administer drugs in the future.

Unlike broad-spectrum chemotherapy agents that can damage healthy cells, asperigimycins appear to specifically disrupt leukemia cell division without affecting healthy tissues. Early tests also suggest the compounds have minimal effects on breast, liver, and lung cancer cells. According to the researchers, this selectivity is important for minimizing unwanted side effects.

In addition to asperigimycins, the team believe similar life-saving compounds may be hidden in other fungal species.

The team are planning to test asperigimycins in animal models, with the eventual goal of launching human clinical trials. And by scanning fungal genomes and exploring more strains of Aspergillus, they hope to unlock new treatments.

“The ancient world is still offering us tools for modern medicine,” said Gao. “The tombs were feared for their curses, but they may become a wellspring of cures.”