Archaeologists in Bolivia have discovered the ruins of a temple that was built by a little-known civilization up to 1,400 years ago.

The temple, called Palaspata after the native name for the area, comes from the Tiwanaku civilization, a predecessor of the Inca Empire. Tiwanaku society disappeared around 1,000 years ago and little is known about the civilization, but these temple ruins shed light on how it may have functioned in its prime. Analysis of the discovery was published June 24 in the journal Antiquity.

“It’s kind of shocking how little we know” about the Tiwanaku, Steven Wernke, an archaeologist and historical anthropologist of the Andean region of South America at Vanderbilt University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. “This finding is quite significant.”

Who were the Tiwanaku?

The Tiwanaku civilization, based just south of Lake Titicaca in the Andes mountains, was extremely powerful at its peak. “It boasted a highly organized societal structure, leaving behind remnants of architectural monuments like pyramids, terraced temples and monoliths,” José Capriles, an anthropological archaeologist at Penn State and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

The society collapsed around A.D. 1,000, leaving only ruins by the time the Incas entered the region about 400 years later.

The Tiwanaku are logistically hard to study, even compared to similar civilizations in the region, like the Wari. Not only are resources for archaeological research limited in Bolivia, but many Tiwanaku sites are at very high altitudes and in remote areas of the Andes. “It’s objectively difficult to document some of these sites,” Wernke said.

Related: 31 ancient temples from around the world, from Göbekli Tepe to the Parthenon

Despite these obstacles, scientists have gleaned some limited information about the Tiwanaku, like the location of its capital and some offshoots of nearby settlements. But understanding the social, economic and political structures of the society has proved trickier.

The biggest debate among experts is how the Tiwanaku state was organized, Wernke explained. Some models posit a ruling class of patrimonial Tiwanaku that oversaw provinces from the capital, while others present the society as a more equitable alliance of diverse peoples across the civilization.

The newfound Palaspata temple

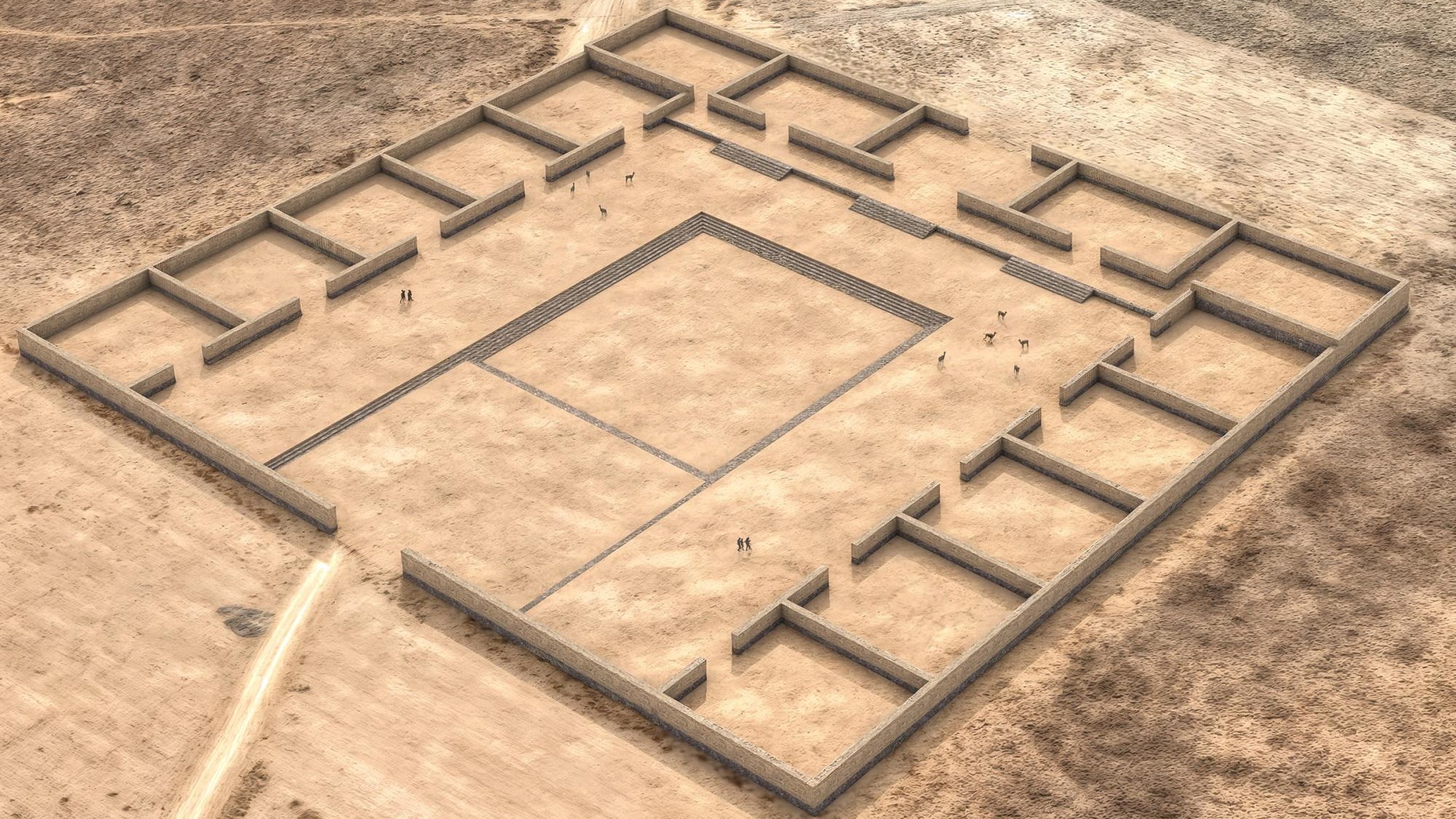

After noticing an unmapped plot of land, the researchers conducted uncrewed flights over the area to get better photos. They then used photogrammetry, a technique that combines many digital photos together to create a virtual 3D model, to construct a detailed rendering of the structure. Their analysis found that the stones’ alignment revealed a terraced platform temple with four-sided rooms arranged around an inner courtyard, according to the statement.

The ruins measure roughly 410 by 475 feet (125 by 145 meters) — about the size of a city block — and their structure seems designed for the performance of rituals around the solar equinox, Capriles said. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal samples from the site showed that it was most intensively occupied from about A.D. 630 to 950, the researchers found.

The Palaspata temple complex, roughly 130 miles (210 kilometers) south of the previously established Tiwanaku archaeological site, was located strategically. It was built in a spot that linked three diverse trade routes — joining highlands to the north, an arid plateau to the west, and valleys to the east — so researchers believe the temple was, in part, meant to connect people from across the society, according to the statement.

Fragments of keru cups, used for drinking a traditional maize beer called “chicha” during celebrations, were found within the ruins. These cups suggest the temple may have been a central hub for trade, Capriles said, because the drink requires ingredients from the relatively distant Cochabamba valleys in central Bolivia.

“This site makes us rethink long-distance connections from Tiwanaku to Cochabamba and further south,” Erik Marsh, an anthropologist at the National University of Cuyo in Argentina who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

The temple also likely had religious significance, Capriles explained. “Most economic and political transactions had to be mediated through divinity, because that would be a common language that would facilitate various individuals cooperating.”

Palaspata supports the model of a coordinated, centralized Tiwanaku societal structure because of its strategic location, Wernke said.

“It presents an enticing and exciting new piece of the puzzle about Tiwanaku and early imperialism in the Andes,” he said. “It’s also certainly not the last piece we’ll hear about.”